The Skinny on Visceral Fat: Why Are Skinny People Dying from “Obese” Diseases, and What Can We Do About It?

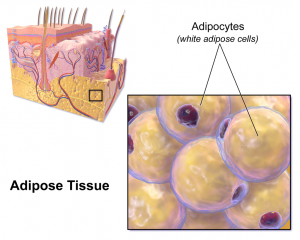

Considering the near-consensus that adipose tissue is the culprit behind so many diseases, one must wonder the reason behind some obese people having no metabolic dysfunction.[1]

The real irony comes with the emergence of a new phenomenon that acknowledges and catalogues those within a healthy BMI range that find themselves at greater risk for diseases generally reserved for those considered obese.

People within the acceptable BMI range have found themselves saddled with heart disease, Type 2 Diabetes, and greater instances of certain cancers.[2] The inquisitive mind must ask why those that are considered low-risk by BMI standards exemplify the results of those considered at high-risk.

These individuals have a pattern of fat storage invisible to the naked eye and hidden deep around the organs and within the liver. Considered visceral fat, visceral adipose tissue (VAT) or intra-abdominal adipose tissue (IAAT), these skinny people are at an increased risk of metabolic diseases despite not being visibly overweight.[3] Also referred to as the thin-fat phenotype,[4] this particular population may be at increased danger of these potential diseases because the issue with visceral fat storage is not visible; it cannot be pinched, or jiggle, or seem unsightly, and so these individuals are not only unaware of the problem, but may even be resistant to the possibility since they do not manifest the outward appearances associated with these issues.

Understanding Visceral Fat

Visceral adipose tissue (VAT) is gaining increasing understanding and acceptance as an active hormone gland with dangerous, destructive potential on the endocrine system.[5] These functions allow it to partly control nutritional intake, hunger, and appetite through secretions of leptin and angiotensin, control insulin sensitivity and inflammation through tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-a), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), resistin, visfatin, adiponectin, and other hormones.[6] With such an impressive list, and such numerous and varied hormone functions, the vital importance of VAT’s endocrine functions becomes apparent. The ignorance or ignoring of this becomes dangerous.

What about normal adipose tissue? When examined and compared side-by-side, VAT proves itself far more dangerous. When compared to total body fat, VAT is significantly better correlated with triglycerides, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, HDL/total cholesterol ratio and its effects on glucose and insulin.[7]

Its intimate control over so many hormonal processes also places VAT in a potential death spiral. Since it acts as both a hunger controller and as a controller of insulin resistance and blood sugar through its release of leptin, resistan, visfatin, and acylation stimulating protein (ASP), visceral fat, in excess, exacerbates the very conditions that allowed it to expand. For example, a sedentary lifestyle and poor diet results in excess visceral fat accumulation. This excess visceral fat then produces excess hormones that signal the body to develop a diseased state such as Type 2 diabetes and insulin resistance. In turn, these disease states trigger their own lifestyle and dietary shifts that result in further visceral fat accumulation. And so spins the disease spiral.

VAT also plays a critical role in the secretion of endogenous growth hormone (GH). As levels of VAT increase, exogenous secretion of GH decreases.[8] As levels of GH drop, VAT increases due to a decrease in hormone-sensitive lipolysis.[9] This becomes more apparent when the use of a GH releasing hormone reverses these effects. A full series of articles is necessary to explain the myriad of potential dysfunctions caused by such endocrine disruption.

Fortunately, clinical treatment with a growth hormone releasing hormone is not necessary. VAT can be safely controlled long-term through intelligent lifestyle alterations and a properly designed training plan.

Fighting Fat With Fat

Unfortunately, there is very little information regarding effective dietary intervention to reduce VAT. However, understanding how integral VAT accumulation depends on endocrine disruption, especially that of hyperinsulinemia, one can intelligently extrapolate this outwards and hypothesize a sensible and logical dietary approach.

Since VAT accumulation depends on hyperinsulinemia and reduced exogenous GH secretion as two major components, we would want to incorporate a diet that controls blood sugar levels (and thus insulin secretion) as well overall improved endocrine function. Removing all sugar, with the notable exception of low-sugar fruits, is the first obvious step. A ketogenic diet has proven itself time and time again, clinically, to controlling hyperinsulinemia, even in those with congenital issues.[10] The ketogenic diet is also efficient at controlling blood sugar levels,[11],[12] and therefore insulin secretion, an excess of which similarly leads to hyperinsulinemia.

A diet that is the opposite of the Standard American Diet (appropriately abbreviated as SAD) is a good direction to go, regardless of the stance of a ketogenic approach.

Exercise Modalities to Combat Visceral Fat

When it comes to exercising with the sole intent of reducing VAT, there are a couple variables one must take into consideration to ensure maximal positive effect.

Per a meta-analysis in 2012 found that moderate or high intensity aerobic training has the highest potential to reduce VAT.[13] Note, too, that this was in the absence of caloric restriction. The type of diet otherwise pursued was not expanded on. One could wonder the potential improvement in outcomes if this same design was followed in combination with the ketogenic diet. Not surprisingly, similar results were found with strength training as well in this same meta-analysis. In this study, “moderate” was defined as >250 min.wk. Of similar importance is the studies analyzed that included greater volume defined as 45-60 minutes a day, six days a week, did not yield more positive results, suggesting a definite bell curve and potential for decrease in return for higher-volume work, an idea supported throughout this section.

This meta-analysis also implied a threshold for training intensity for VAT to be effected optimally. Unfortunately, no further evidence is described for this, other than mentioning the synergistic qualities of high-intensity training post-exercise.[14]

One must use caution with the word “aerobic”, however, as the effect of regular aerobic exercise, defined as walking and jogging at a moderate intensity on body fat is negligible.[15],[16] Perhaps this explains why so many people find themselves on treadmills and elliptical, performing steady-state aerobic exercise with little or no improvement.

High intensity training demands special mention here due to increased GH secretion.[17] In this same study, GH concentration was still ten times higher than baseline an hour after recovery. Harkening back to the relationship between VAT and reduced GH secretion, this method of training directly counteracts one of the most damning results of excess VAT and could single-handedly upset one of the mechanisms behind VAT accumulation.

Since Type 1 diabetics are prone to experiencing hypoglycemia after prolonged aerobic expenditure, a single 10-second sprint could help retain healthy sugar levels.[18] This opens a potential exercise prescription for a population group that otherwise would be at a higher risk. Obese women with metabolic disorder were studied under a high-intensity exercise training and low-intensity exercise training, with the HIET group showed significantly reduced abdominal fat, abdominal subcutaneous fat, and visceral fat, where no significant changes were found in either a control group or the low-intensity group.[19] The last thing a medical fitness expert wants to do is waste time with an ineffective approach.

Since Type 1 diabetics are prone to experiencing hypoglycemia after prolonged aerobic expenditure, a single 10-second sprint could help retain healthy sugar levels.[18] This opens a potential exercise prescription for a population group that otherwise would be at a higher risk. Obese women with metabolic disorder were studied under a high-intensity exercise training and low-intensity exercise training, with the HIET group showed significantly reduced abdominal fat, abdominal subcutaneous fat, and visceral fat, where no significant changes were found in either a control group or the low-intensity group.[19] The last thing a medical fitness expert wants to do is waste time with an ineffective approach.

Numerous studies also highlight the effectiveness of HIIE over steady-state aerobic exercise for reduction of adipose tissue and VAT. Tremblay et al. compared HIIE and aerobic exercise and found that the HIIE group lost more subcutaneous fat after 24 weeks than the aerobic group.[20]

Another study by Trapp et al. once again found that women in the HIIE group lost 2.5kg more subcutaneous fat than those in a steady-state aerobic program.[21]

The Slimmed-down Version

All this information implies that although VAT has numerous mechanisms to harm the body and exacerbate disease states, the appropriate modifications to training and lifestyle can help the body against it without the use of drugs. The optimal exercise prescription rests with a mixture of moderate and high-intensity training combined with intelligent diet. Thankfully, despite its horrible potential, managing visceral fat is not so difficult a task. As fitness professionals, we can utilize this information to ensure that we do not get stuck in an archaic steady-state paradigm and can better serve our clients.

Shane Caraway CHN, CPT, PTSP, uses his education, experience, and credentials as a certified personal trainer and nutritionist to help others recapture the primitive mystique, strength, and beauty that their body is capable of. His greatest pleasure comes from the successes of his clients, no matter how mundane or simple each small victory may be. Always in pursuit of various techniques, compounds, nutrients, herbs, and other means to help support the body against disease, Shane finds the challenge of combating chronic disease to be the pinnacle of his work, especially with diseases and conditions that otherwise cause clients to surrender.

References

Adipose tissue image: Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014″. WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436

[1] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Exercise%2C+abdominal+obesity%2C+skeletal+muscle%2C+and+metabolic+risk%3A+evidence+for+a+dose+response.

[2] http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/14274/

[3] http://westminsterresearch.wmin.ac.uk/14274/

[4] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/51618462_The_thin-fat_phenotype_and_global_metabolic_disease_risk

[5] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3648822/

[6] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3648822/

[7] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=Exercise%2C+abdominal+obesity%2C+skeletal+muscle%2C+and+metabolic+risk%3A+evidence+for+a+dose+response.

[8] http://europepmc.org/articles/PMC4324360

[9] http://europepmc.org/articles/PMC4324360

[10] https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-015-0342-6

[11] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2716748/

[12] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3506983/

[13] http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0056415

[14] http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0056415

[15] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2991639/?_escaped_fragment_=po=6.25000

[16] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19175510

[17] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2991639/?_escaped_fragment_=po=6.25000#B1

[18] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2991639/?_escaped_fragment_=po=6.25000#B1

[19] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2730190/

[20] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8028502

[21] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18197184