The Hip Complex: Understanding the Science Behind Both Movement and Dysfunction

Introduction

The foot is where movement begins requiring mobility to initiate daily and sport specific movements. However, the knee however, requires stability with daily movements, but more importantly, dynamic sport movements such as soccer or football. The hip, like the ankle, requires mobility, to perform such simple movements as sit to stand, climbing stairs and other functional movements. In this article, we will review the anatomy of the hip, common injuries to the hip, functional assessments and training strategies to work with clients with previous injuries.

Hip joint with supporting ligaments

Let’s look at the basic anatomy of the hip. The hip joint is a multi-axial ball and socket joint between the femoral head and the acetabulum, similarly to the shoulder joint. The hip is surrounded in white, several ligaments that provide support and stability.

The labrum attaches to the acetabulum deep within the socket between the femur and acetabulum. The joint is covered by a capsule blended with three strong ligaments: iliofemoral or “Y” ligament, which resists extension, the ischiofemoral ligament, which resists extension and internal rotation, and the pubofemoral ligament, which resists abduction.

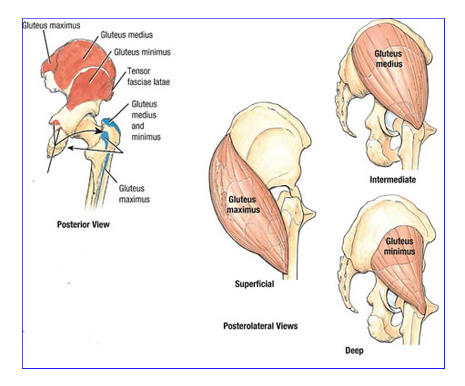

Muscularly, the glute medius and minimus are located along the anterolateral aspect of the hip to stabilize in the frontal pane, whereas the glute maximus, is located in the sagittal plane posteriorly to facilitate hip extension.

Supporting muscles around the hip

Common injuries and causes

There are different types of injuries the hip can sustain. The most common are the hip osteoarthritis, iliotibial band syndrome and total hip replacement. In this next section, we will review each condition providing a deeper understanding of each.

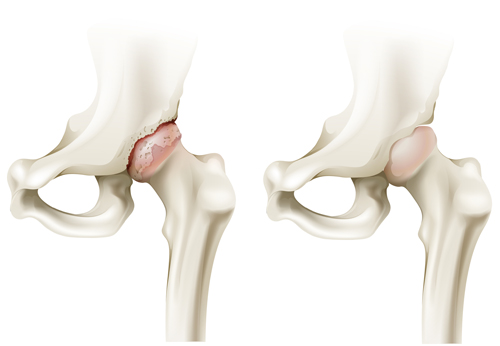

Osteoarthritic hip on left, normal hip on right

a. Hip osteoarthritis(OA)

Mechanism of injury/pathophysiology: A degenerative process of varied etiology which includes mechanical changes within the joint. O.A. affects some 40% of those aged over 65 in the community may have symptomatic OA of the knee or hip(Zhang, W. et al 2007).

Pathophysiology: Osteoarthritis (OA) is a relatively common musculoskeletal disorder, with a high prevalence that increases with age. O.A. is a degenerative process of varied etiology, which includes mechanical changes within the joint (Pisters, M., et al 2007).

Risk Factors: Excessive weight born on hip joint, muscle imbalance, repetitive stressors.

Sign and symptoms: Pain in the a.m. described as “achy” that decreases as the day progresses, pain with weight bearing or walking, difficulty squatting, and lateral thigh discomfort. Patients will describe of pain and stiffness in the a.m. described as “achy.” During the day, movement and activity, improves mobility and activity(Fernandes, L et al 2010). However, the volume of activity if too much, will increase pain. Patients typically have pain with weight bearing or prolonged walking, difficulty squatting, and lateral thigh discomfort.

Medical treatment: Non steroidal (NSAIDS)(examples are Ibuprofen/Advil).

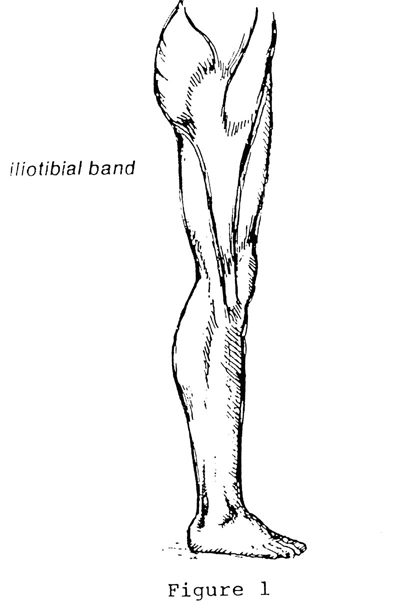

Iliotibial band syndrome

b. Iliotibial band syndrome(ITB)

Mechanism of injury: Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) is a common injury of the lateral(outside) aspect of the knee particularly in runners, cyclists and endurance sports. ITBS is the most common running injury(Ellis, R et al 2007).

Pathophysiology: ITB syndrome is a non-traumatic overuse injury caused by repetitive friction/rubbing of the distal(farthest) portion of the iliotibial band (ITB) over the lateral femoral epicondyle with repeated flexion and extension of the knee.

Contributing/Risk Factors:

• Muscle imbalances/weakness: per the research and my clinical experience, hip flexors and quadriceps are stronger and than the hamstrings.

• Shoe support-important to rotate running shoes every 6 months or 500 miles according to multiple podiatrists I have worked with over the years.

• Increased bouts of running, altered foot mechanics-ie. Orthotics or need for orthotics.

• Lack of stretching, particularly tight ITB, hip flexors and quadriceps. Contributes to increasing compression along the outer hip.

Sign and symptoms: Lateral knee pain over the lateral condyle of the femur described as “dull/achy” that gradually develops & worsens particularly with running. Pain then becomes “sharp” in nature.

c. Total hip replacement

Mechanism of injury: Osteoarthritis is a musculoskeletal condition that develops over time affecting primarily the hip and knee joints. O.A. affects some 40% of those aged over 65 in the community may have symptomatic OA of the knee or hip(Zhang, W. et al 2007).

Pathophysiology: Osteoarthritis (OA) is a relatively common musculoskeletal disorder, with a high prevalence that increases with age. O.A. is a degenerative process of varied etiology, which includes mechanical changes within the joint (Pisters, M., et al 2007). Significant pain, decreased mobility and compromised function, are the primary reasons, a person would typically undergo a total joint arthoplasty(joint replacement). Total joint arthroplasty is a highly efficacious and cost-effective procedure for moderate to severe arthritis in the hip(Santaguida, P. et al 2008).

Common assessments

A simple functional test to assess a client’s movement pattern, is the squat. The squat is a classic fundamental primal movement that someone typically performs almost on a daily basis. With this test, you can observe how the client’s ankle, knee, hip and back moves compared to normal movement patterns.

What am I looking for?

The approach to assessment is all about asking and answering questions about movement:

• How does the client start, finish the movement?

• What strategies do they use? Do they have the appropriate flexibility to perform the movement?

• Is stability a problem? Are there compensations elsewhere in the movement sequence?

How do I interpret the movement?

• It is important to observe the client in both the frontal and sagittal planes

• Observing globally first, then examine how the entire kinematic chain is working as it relates to timing and sequence to achieve the movement

Dynamic Movement Assessments

1. Functional squat

The squat is a classic fundamental primal movement that someone typically performs almost on a daily basis. Whether it is to perform to pick something up or move an item. Therefore, it is important to assess the movement pattern a client uses during this movement.

Squat in frontal view; Squat in side view

What is required in a squat?

• Adequate ankle mobility, knee stability, hip mobility, lumbar spine(lumbo-pelvic junction) stability

In place lunge

Observations:

• Note the overall quality and range of movement in the frontal plane and sagittal plane

• Note the symmetry or lack of symmetry with the movement

• Note the point of transition from descending to ascending

• Note if there is an shaking(juttering), which indicates weakness in the lumbo-pelvic junction affecting the entire kinematic chain

Another simple assessment is an in place lunge, which examines one’s control through the entire kinematic chain. The lunge is another fundamental primal movement. The lunge is a dynamic movement that is typically performed during daily activities (stooping down to pick something up) or as part of an athletic movement. This test examines ankle control, knee control and pelvic movement in the sagittal plane.

Training strategies and programming for hip injuries

With any injury, the most important thing to remember is the type of injury, healing time and prior level of function of the client. Let’s begin with ankle sprains.

SLS stance with TRX

a. Hip Osteoarthritis(O.A.)

ITB stretch

Recommendations for training: Aqua therapy has been shown in the research to significantly reduce pain, improved physical function, strength, and quality of life(Hinman, Rana S., et al 2007), stretching ITB, hip flexors, quadriceps and hamstrings, strengthening weaker hip abductors(glute medius/minimus). Strengthening specifically hip abductors in various studies when compared to general strengthening, resulted in significant reduction in knee pain, objective change in functional outcome tests, physical function and daily activities(Bennell, K.L., et al. 2010 & Hernández-Molina, G et al. 2008). Core strengthening should also be an integral part of the training program.

b. ITB Syndrome

Recommendations for training: Important to keep stretching the ITB after exercise. Client education on the changing of running shoes every 500 miles or 6 months is key. Resistance training should focus on strengthening weaker phasic muscles (glute medius, minimus and maximus), which are required to stabilize and push off during running. Dynamic core strengthening should always play an integral role of training. Use of aqua therapy can be extremely beneficial and relaxing. It is very important to educate the client on the importance of cross training(ie. yoga, pilates, hiking, and swimming to condition the lower extremity muscles.

c. Hip replacement(THR)

Bridging with physioball

Recommendations for training: Prior to commencing training, it is important to clarify with client, that there are no other underlying health issues. Important to follow hip precautions: avoidance of crossing affected leg towards midline(adduction), and squatting past hip flexion 90 degrees. Training should focus on strengthening weak glute medius/minimus, glute maximus and hamstrings. Effective and safe exercises include; in place lunges, diagonal lunges, seated leg extension and seated leg curl machine. Core strengthening should also always begin with static exercises, and then progressed to dynamic accordingly. Safe and effective core strengthening exercises include; standing trunk rotation with tubing or cable, four point planks, and side planks. Safe dynamic core strengthening exercises include bridging with physioball, single leg bridge with physioball, traveling forward lunge with medicine ball trunk rotation, and four-point plank on physioball as examples.

Summary

The hip is a complex unit thitbdat is comprised of a multitude of ligaments, tendons, connective tissue, muscles that synergistically initiate and correct movement, and stabilize when an unstable environment. Understanding the anatomy, biomechanics and weak links of the hip, common injuries and evidenced based training strategies, should provide you with the insight to better understand and work with clients with these kind of injuries more confidently.

Written by Chris Gellert, PT, MMusc & Sportsphysio, MPT, CSCS, AMS.

Chris is the CEO of Pinnacle Training & Consulting Systems (PTCS). A continuing education company, that provides educational material in the forms of home study courses, live seminars, DVDs, webinars, articles and min books teaching in-depth, the foundation science, functional assessments and practical application behind Human Movement, that is evidenced based. Chris is both a dynamic physical therapist with 14 years experience, and a personal trainer with 17 years experience, with advanced training, has created over 10 courses, is an experienced international fitness presenter, writes for various websites and international publications, consults and teaches seminars on human movement.

REFERENCES

Bennell, K.L., et al. 2010, ‘Hip strengthening reduces symptoms but not knee load in people with medial knee osteoarthritis and varus malalignment: a randomized controlled trial,’ Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, vol. 18, issue 5, pp. 621–628.

Ellis, R., et al., 2007, ‘Iliotibial band friction syndrome—A systematic review,’ Manual Therapy, vol. 12, pp. 200–208.

Fernandes, L., et al 2010, ‘Efficacy of patient education and supervised exercise vs. patient education alone in patients with hip osteoarthritis: a single blind randomized clinical trial,’ Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, vol. 18, issue 10, pp. 1237–1243.

Goodman, Catherine., Boissonnault, William., 1998, G. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist, W.B. Saunders Company, Philadelphia, pp. 267-274, 279-292, 318-328, 412- 417, 609-610, 614-615, 617-621, 660-667, 736-745, 748-755.

Hernández-Molina, G et al. 2008 ‘Effect of therapeutic exercise for hip osteoarthritis pain: Results of a meta-analysis,’Arthritis Care & Research, vol. 59, issue 9, pp. 1221-1228.

Hinman, Rana S., et al 2007, ‘ Aquatic Physical Therapy for Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: Results of a Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial,’ Journal of Physical Therapy, vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 32-43.

Pisters, M., et al., 2007, ‘Exercise adherence improving long-term patient outcome in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee, Arthritis Care & Research, vol. 62,

Santaguida, P. et al 2008, ‘Patient characteristics affecting the prognosis of total hip and knee joint arthroplasty: a systematic review,’ Canadian Journal of Surgery, vol. 51, issue 6, pp. 428-436.

Zhang, W., et al., ‘OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part I: Critical appraisal of existing treatment guidelines and systematic review of current research evidence,’ Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, vol. 15, issue 9 pp. 981–1000.