Osteoarthritis (OA), the most common form of arthritis, affects some 27 million adults per year and is on the rise. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that in 2005, self-reported arthritis or other chronic joint symptoms affected approximately 21.4 million Americans aged 65 years and older. This estimate is expected to reach 41.1 million by 2030. Osteoarthritis makes simple movements and activities of daily life painful and difficult to perform.

Osteoarthritis typically occurs in the hands, knees, spine and hips affecting a multitude of joints. Those affected with OA will typically complain of symptoms of stiffness, low-grade inflammation and pain. This stiffness and pain are most prevalent in the morning which improves with activity and as the day progresses.

Pathology

The cause of OA involves a combination of mechanical, cellular and biochemical changes. The processes involves changes in the composition and mechanical properties of the articular cartilage. Cartilage is comprised of water, collagen and proteoglycans, In healthy cartilage, there is continual remodeling that occurs as chrondocytes (cartilaginous cells) replace macromolecules that are lost through degradation. In Osteoarthritis, this process is disrupted leading to degenerative changes and abnormal repair response. 2

Contributing Factors

Despite increasing awareness of the negative effects of obesity on health and OA in particular, the prevalence of individuals who are overweight or obese is increasing. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) collected between 1999 and 2000 show that 64.5% of the US population is overweight, including 30.5% classified as obese. Carrying extra weight places biomechanically places increased stress and force on the weight bearing joints. Other common risk factors include joint injury, mechanical stress, history of immobilization and trauma.

Medical Management

Arthritis treatment first begins with education. Treatment for osteoarthritis can help relieve pain and stiffness, however the condition can progress. Physicians will tend to focus to help those afflicted with OA by helping patients manage their pain. There are several ways to do this. The first commonly used approach is pharmacologic intervention. Traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs(NSAIDs) have been shown to be effective for OA pain, and are perceived as second-line drugs for the treatment of mild to moderate OA.

Physical therapy is very effective in helping those suffering with OA. Where the focus is on helping the patient by improving their muscle flexibility, joint mobility and strengthening the weaker hip musculature. Resulting in improved mobility, function, decrease pain and improved quality of life.

Training Recommendations

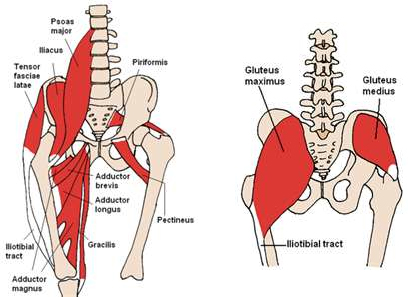

Because arthritis is a “process,” the most effective training is education and prevention. From a cardiovascular perspective, a cardiovascular program should be tailored to the client. A recumbent or stationary bike is a great starting point to reduce the load to the hips and knee which can be progressed to the elliptical machine. Stretch the tight (postural) hip flexors and quadriceps seen in figure one will reduce the load to the knee joint. Yoga can also be an effective intervention which will improve flexibility, balance, strength and body awareness. Strength training should focus on targeting the weaker phasic muscles; glute maximus, glute medius/minimus as seen in figure two. These muscles are necessary for everyday movements such as arising from a chair, climbing stairs, and negotiating uneven surfaces.

Figure 2. (right) Posterior muscles of the hip complex

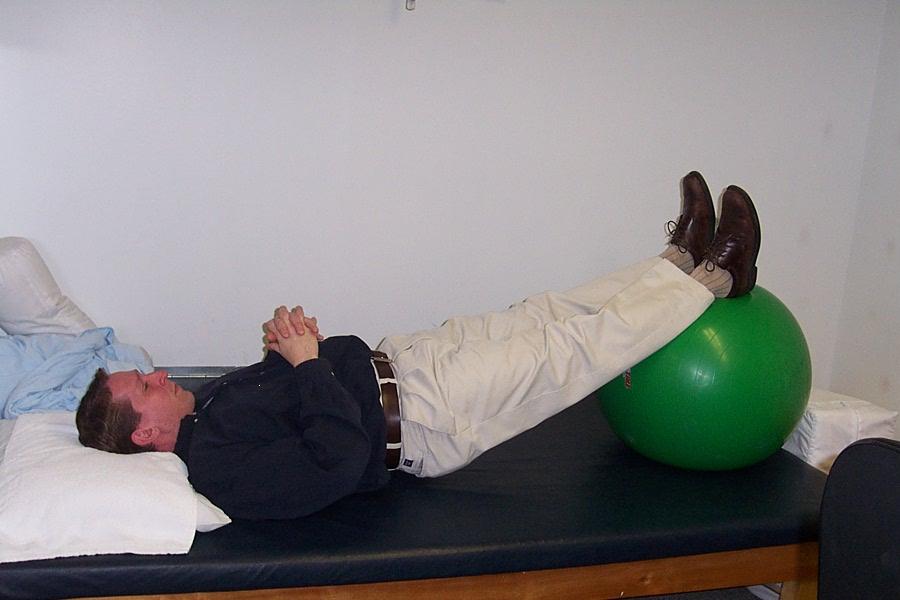

Strengthening the core begins with simple exercises such as bridging with the ball (figure three), targeting glute maximus, hamstrings, and the lower back musculature. This can be progressed to having the client hold longer or to perform a single leg bridge. Functional strengthening exercises such as reverse lunges holding a medicine ball that can be progress to either holding overhead or adding trunk rotation will do two things. four and figure five). The use of aqua therapy can also be effective which eliminates gravity resulting in a client’s ability to strengthen their lower body in a relaxed environment.

Figure 5. (right) Diagonal lunge with trunk rotation with medicine ball

Summary

Arthritis continues to affect many individuals for various reasons. One thing is certain, knowledge, prevention and early screening is fundamental. Understanding the pathological process and medical approach is the first step in helping your clients with OA. Refreshing yourself on anatomy, biomechanics and understanding proper exercise prescription is fundamental. Any exercise program should be individualized resulting in improved function.

Chris Gellert, PT, MMusc & Sportsphysio, MPT, CSCS, C-IASTM, NASM CPT. Chris is the President of Pinnacle Training & Consulting Systems, LLC. A consulting and education company that is committed to creating and providing evidenced based educational material in the form of home study courses, dynamic live seminars, mini-books, DVD’s on the areas of; human movement, fitness and rehabilitation with unique practical application. Chris has 20 years clinical experience having worked with primarily orthopedic patients, spinal injuries, post-surgical conditions, traumatic and sport specific injuries and 20 years as a personal trainer. For more information, please visit www.pinnacle-tcs.com.

REFERENCES

- David M Lee et al. Rheumatoid Arthritis. The lancet. Vol. 358. September 2001. pp: 1240-1242.

- Hinton et al. Osteoarthritis: Diagnosis and Therapeutic Considerations. Journal of American Family Physician. 65(5) Pgs: 841-849. 2002.

- Weinblatt ME, Maier AL, Fraser PA, Coblyn JS. Long-term prospective study of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: conclusion after 132 months of therapy. Journal of Rheumatology. 25: pp: 238–42. 1998.

- Kremer JM. Safety, efficacy, and mortality in a long-term cohort of patients withs rheumatoid arthritis taking methotrexate: follow-up after a mean of 13·3 years. Arthritis Rheumatology. 40: pp: 984–85. 1997.

- Tugwell P, Wells G, Strand V, et al. Clinical improvement as reflected in measures of function and health-related quality of life following treatment with leflunomide compared with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: sensitivity and relative efficiency to detect a treatment effect in a twelve-month, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 43: pp: 506–14. 2000.

- Schneider, Rayfel. Et al. Rheumatology Disorders Clinics of North America. 28. pp: 503–530. 2002.

- Braun, Jurgen et al. Ankylosing Spondylitis. The Lancet. 369, 9570; Research Library. pp. 1379. 2007.

- Ding, T., Deighton, C. Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Journal of Medicine. Volume 38. Issue 4. 2009. pp: 172-1769.

- Calin, A. Ankylosing Spondylitis. Journal of Medicine. Volume 34. Number 10. pp: 396-399. 2006.

- Litman, D. Maximizing Success in Osteoarthritic Care: Benefits of a comprehensive Management Approach. Internet Journal of Rheumatology. Volume 5. Issue 2. pp: 1-2. 2008.