Colorectal Cancer Development and Nutritional Deficits Management

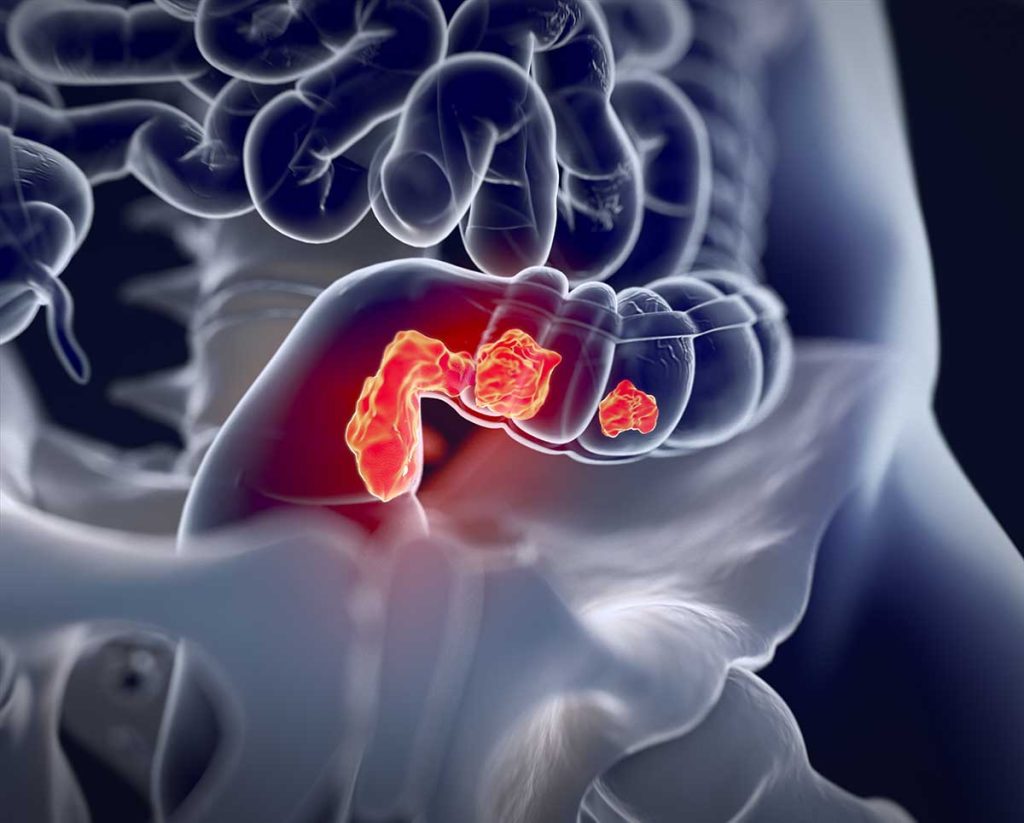

On an annual basis, a number of Americans are diagnosed with some form of cancer. One of the most commonly occurring cancers that is recognized as the third deadliest cancer in America and the world is colon cancer, or colorectal cancer (CRC).1 CRC is first known to present as cancer of the colon and rectum which generally affects older adults. The incidence and mortality rate of CRC can increase with age with the median age of diagnosis at 70 years within developed countries.2 However, there is the potential for the cancer to impact individuals of all ages.

There are also potential risk factors for development which can include male sex, excessive alcohol intake, smoking, and lack of physical activity to name a few.2 Given the current and increasing rate of CRC diagnosis, there has been ongoing promotion of preventative measures and treatment interventions once formal diagnosis has been made.3

There are a number of recommendations for dietary measures to prevent colorectal but once diagnosed, nutritional support is also needed. For any person who is suspected of having CRC, there are both signs and symptoms to be aware of. Many patients can be symptomatic for several months before presentation. Some of the more common findings include rectal bleeding, changes in bowel habit, or loss of appetite and fatigue.4 The loss of appetite that can be associated with CRC can present with nutritional deficits. Given that the primary function of the colon is to aid with the absorption of electrolytes and fluids, the diagnosis of CRC and the treatment interventions that can be applied can impact nutritional absorption. The treatment of colorectal cancer can increase the demand for nutrients so during treatment it is important for patients to adhere to a healthy diet to nourish their bodies.

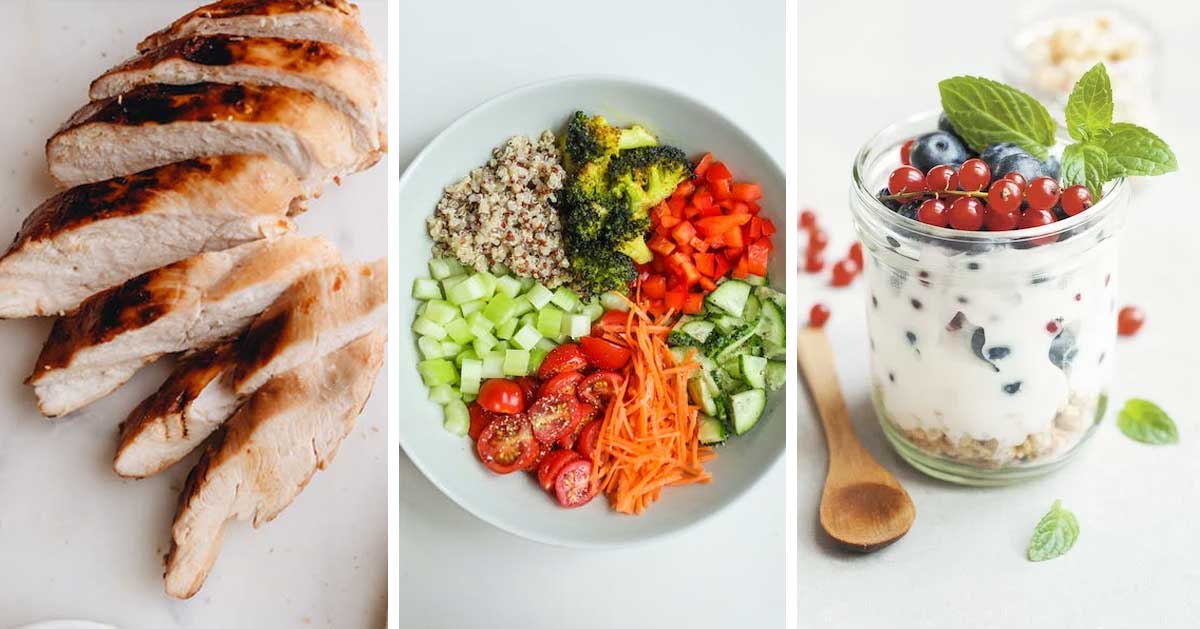

The mainstays for nourishment can be obtained from proteins, consumption of healthier fats, consumption of whole grain goods, fruits and vegetables, and intake of adequate amount of water given the potential for dehydration to occur.5 Additionally, according to the American Cancer Society, the following foods are recommended for those who are undergoing colon cancer treatments: plant based foods, fruits and vegetables that contain essential vitamins and antioxidants, and healthy snacks (like Greek yogurt or lean chicken).6 If there are instances in which tolerability issues arise with the consumption of these types of foods, it is important for a patient to immediately discuss this matter with their provider.

A diagnosis of CRC can impact a person’s health and life in a significant way. During the course of the condition and the timeframe for therapeutic interventions, it is important to monitor the nutritional needs of the person. The potential for nutritional deficits to occur can be significant with CRC, so a clear, focused plan should be developed with the best course of action in mind to minimize any negative impact. While the goal is always for primary, secondary, and tertiary preventive strategies, it is also important to know how to appropriately address issues such as nutrimental deficits that can arise with the given diagnosis.7 The recognition of nutrition as a key element to improved treatment outcomes should also be addressed with its comes to comprehensive CRC management.

Abimbola Farinde, PhD is a healthcare professional and professor who has gained experience in the field and practice of mental health, geriatrics, and pharmacy. She has worked with active duty soldiers with dual diagnoses of a traumatic brain injury and a psychiatric disorder providing medication therapy management and disease state management. Dr. Farinde has also worked with mentally impaired and developmentally disabled individuals at a state supported living center. Her different practice experiences have allowed her to develop and enhance her clinical and medical writing skills over the years. Dr. Farinde always strives to maintain a commitment towards achieving professional growth as she transitions from one phase of her career to the next.

References

- Marley AR, Nan H. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer. Int J MolEpidemiol Genet. 2016;7(3):105-114. Published 2016 Sep 30.

- Brenner H, Chen C. The colorectal cancer epidemic: challenges and opportunities for primary, secondary and tertiary prevention. Br J Cancer 119, 785–792 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-018-0264-x

- Holowaty EJ, Marrett LD, Parkes R, Fehringer G, editors. Colorectal Cancer in Ontario 1971-1996 [Internet] Cancer Care Ontario; 1998 [14 June 2016] Available from: https://www.cancercare.on.ca/common/pages/UserFile.aspx?fileId=13718.

- Thanikachalam K, Khan G. Colorectal Cancer and Nutrition. Nutrients. 2019;11(1):164. Published 2019 Jan 14. doi:10.3390/nu11010164

- Claghorn K. Colon,rectal, and anal cancer: Frequently asked nutrition questions. OncoLink.February 9, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2022.

- Kubala J. A diet plan for before and after colon cancer treatment. Healthline.June 7, 2021. Accessed January 20, 2022.

- Brenner, H., Altenhofen, L., Stock, C. &Hoffmeister, M. Prevention, early detection, and overdiagnosis of colorectal cancer within 10 years of screening colonoscopy in Germany. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.13, 717–723 (2015).