Bilateral Coordination: The Gateway to Successful Movement | Part 1

“You want me to do what?” says Susan when she hears the drill that I want her to complete during our exercise class.

“You’ve gotta be kidding me! Where do you come up with these drills? You DO remember I have Parkinson’s Disease?” To which I smile and reply, “Yes, and you can do this, I promise!!”

Susan rolls her eyes and jokingly replies, “Right, I guess we’ll just have to see about that, Colleen!”

“You can do this Susan,” I reply, “but it is going to require work, and I’ll be right here to help you.”

You may be thinking to yourself, what kind of drill is Colleen asking her client to perform? Could it be a 150lb deadlift? Maybe it’s a 5ft plyo-jump on one leg or possibly a 3 minute plank? Not even close! While the deadlift, jump and plank are all fantastic exercises, I’m asking Susan to do a lunge series with lateral arm lift series which incorporates Bilateral Coordination.

Bearfoot OT and Noémie von Kaenel, OTS share that bilateral coordination is the integration and sequencing of movement by using “two parts of the body together for motor activities”.

“To coordinate two-sided or bilateral movements, the brain needs to communicate between both its hemispheres through the corpus callosum which we will discuss later on. But it is important to note that this area of the brain develops at 20 weeks but connections between the two hemispheres strengthen and develop as a child develops . Bilateral coordination is also closely linked to the vestibular system (where your head is in space), posture, and balanced movements.”

For example: We all grew up challenging our friends to pat their head and rub their tummy at the same time. Then switch hand placement and repeat. Take a second and give it a try! Did you find one hand placement easier than the other? Now, imagine that you have Parkinson’s Disease (PD) and you’ve been given this challenge. You would probably tell me that it was tough on both sides. Why is that?

Let’s take a few moments and discuss Parkinson’s Disease so you understand the challenge of Bilateral Coordination.

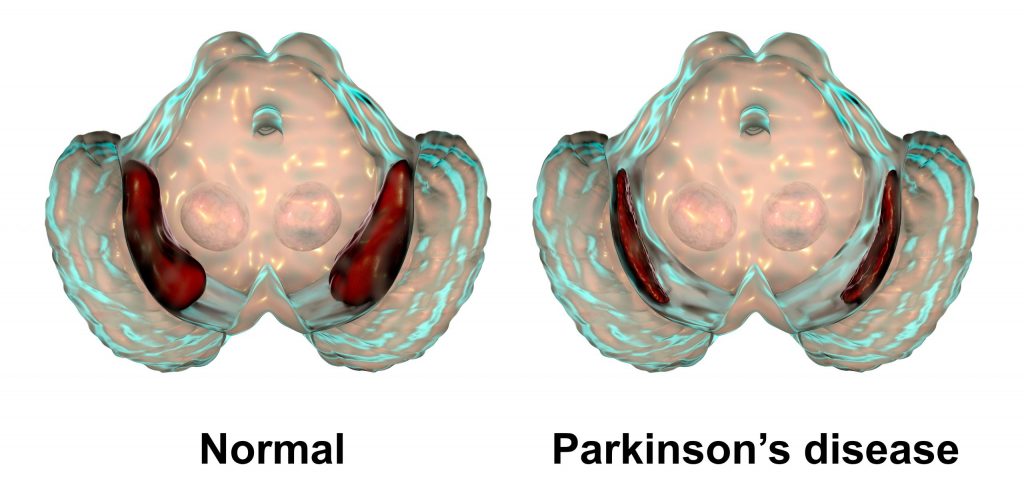

By definition, Parkinson’s Disease is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects predominantly dopamine-producing neurons in the Substantia Nigra (SN) (Latin for “Black Substance”, due to its darkened pigment in the brain). The substantia nigra contains the highest concentration of dopamine neurons. It is a part of the Basal Ganglia, an area responsible for motor control, motor learning, and procedural memory, such as learning how to tie your shoes.

Substantia Nigra in Normal Brain vs. Parkinson’

Without the Substantia Nigra, the brain and body simply do not communicate as well, or at all depending on the stage of PD. To us, fitness professionals, we observe those living with Parkinson’s Disease displaying uncoordinated movements, loss of balance, poor gait, postural issues, visual tracking problems, rigidity, tremor, freezing, facial masking, inability to focus on a task or process information clearly, bradykinesia, hypophonia (volume of voice)… and as it pertains to Bilateral Coordination, the challenge to perform a drill with one side of the body such as the left arm while moving the right leg. Now your wheels are turning and you are probably asking yourself…

Why Is Bilateral Coordination Important?

Bilateral Coordination requires your small and large motor and visual-motor functioning to work together making it possible to accomplish ALL of your daily tasks! For example, in order to write your grocery list on a piece of paper, you need to hold the paper with one hand while writing the note at the same time.

Proprioception or body awareness is another great reason to work on Bilateral Coordination. Throughout our entire life, we have the ability to know where our body is in time and space. For the person living with Parkinson’s Disease, this means a lower risk of falling, and believe me, that is crucial!

What Is The Scientific Explanation Of Bilateral Coordination?

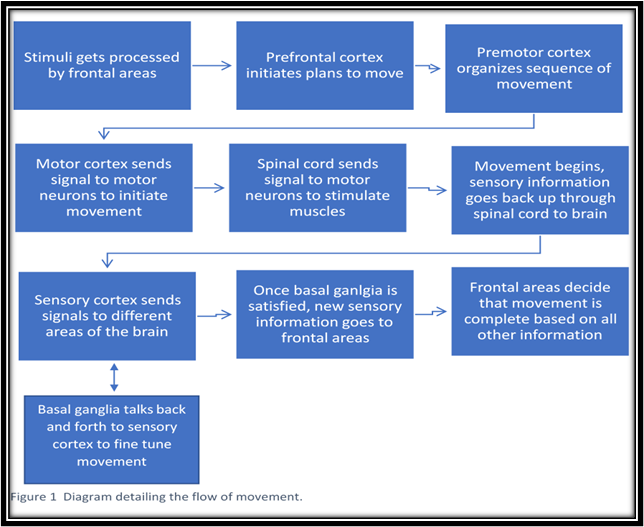

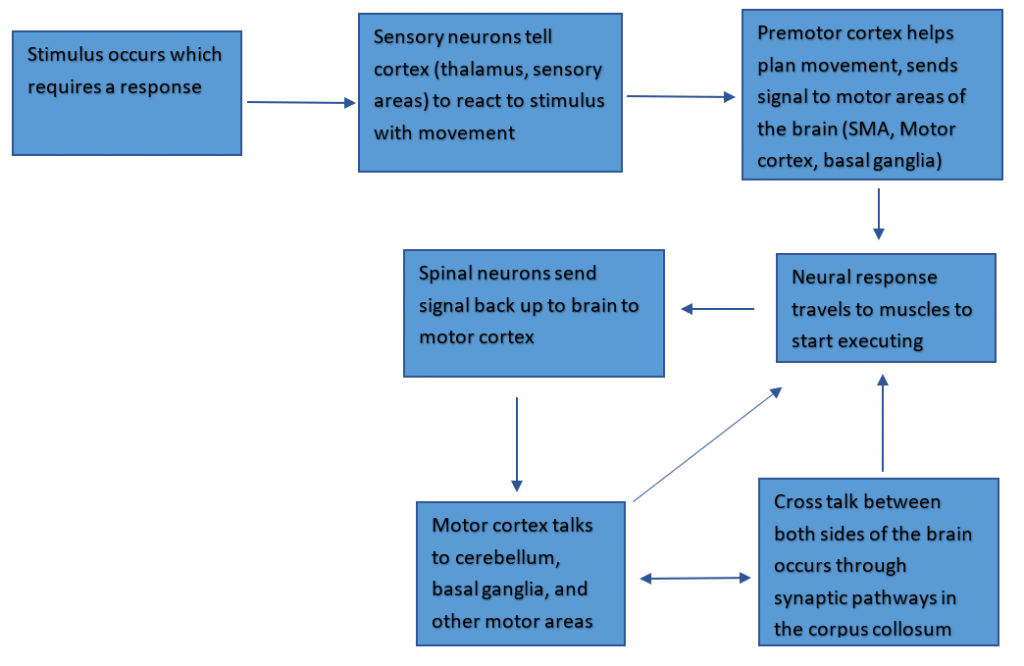

We learned in a previous article, “How a Thought Becomes an Action”, that motion in the brain is complicated and there are numerous steps to ensure that the motion in the brain is coordinated and precise. This all starts in the motor cortex, goes through the spine into motor neurons and muscles, and goes back into the brain to be fine-tuned by the basal ganglia (keep in mind this is where the substantia nigra resides). But now we’re adding onto this process by adding on even more coordinated movement in:

- The premotor cortex

- Supplementary motor area

- The cerebellum

- And the corpus callosum

Each one of these areas works in tandem with the movement pathways we discussed previously to produce bilateral movement and is the reason that I can type and you can read this paper right now. Let’s go over what each of these areas does, starting with the premotor cortex (Figure 1, below).

Fig. 1 The neural pathway from stimulus sensation to movement response.

- The premotor cortex is more involved in the planning of movement rather than the execution is important for bilateral coordination in movements even as simple as walking.

- When walking, the premotor cortex would be important for planning the gait length required to keep our balance, the speed, and overall how the movement is going to go so we don’t crumple or trip over our own feet (to some extent anyway…)

- The supplementary motor area (SMA) is also involved in planning movement, but in a different way.

- The SMA is planning for movements both ipsilaterally (scientific jargon for same-side), and contralaterally (scientific jargon for different-side).

- While the premotor cortex is planning for what muscles have to move to do the actual action, the SMA is controlling which sides are going to go first to maintain balance and what makes the most sense given the environment we would be walking in.

- The SMA is planning for movements both ipsilaterally (scientific jargon for same-side), and contralaterally (scientific jargon for different-side).

- The cerebellum is less involved in conscious movement but is extremely involved in coordination and balance, which is needed for performing tasks bilaterally.

- When walking, we need our brain to fine-tune the balancing and counterbalancing errors (such as arm swing), which happens in the cerebellum. Think of the cerebellum like an editor. The movement keeps happening, and each time it keeps getting better and easier because of the error calculations the cerebellum makes.

- The corpus callosum, which works in tandem with the rest of the cortex to send signals to the different halves of the brain.

- What happens on one side doesn’t always translate to the other side, which is where the corpus callosum comes in. Each side has its own control mechanisms for the opposite side of the body (talk about contralateral). The corpus callosum is the phone line that connects these two hemispheres so they can talk to each other and get the messages for both sides of the body into a beautifully coordinated orchestra of neuronal firing and muscle movements.

So given these four areas of the brain, along with the rest of the movement pathway, there are numerous elements here contributing to sensory integration, planning of movement, checkpoints for these movement executions, and a miscommunication playing out on both sides of the brain. This means that there are a lot of alternate pathways in case anything goes wrong. However, pathways can deteriorate over time, and problems can arise. Which brings us to PD, and the issues that may happen in bilateral coordination as the disease progresses.

How Does Bilateral Coordination falter in the PD brain?

There’s a lot of different attributes to movements like walking – a complicated movement with a number of variables:

- First, you have to start walking.

- Because it requires a lot of input all at once, it’s hard for the brain to do subconsciously, especially for someone who has PD. similar to revving a car for the first time after stopping at a red light.

- Then you have sensory cues.

- These can be challenges like incline or decline, which determines how much effort you need to stay upright, stay up to speed, and how much force you need to put into your step to keep up with gravity (like a driver constantly paying attention to the road).

- Once you start walking, your brain can put less effort into what researchers call “steady-state walking”, where your legs follow the same instructions repeatedly, similar to coasting on a highway (2).

- Next, we get to turning, where walking requires more input such as:

- Balancing on one leg while pivoting the other

- Slowing down, and speeding back up again (all while navigating those sensory cues, mind you), which is where a lot of the times this bilateral coordination seems to freeze up in PD, hence the clinical symptom called freezing of gait (FOG).

- Thinking again of the car analogy, this is akin to having to slow down and turn the wheel the proper amount so you don’t hit the curb but you make it to the proper lane, speeding back up again.

With all those steps, anything that goes wrong will hurt the body’s ability to keep steady and coordinate larger and smaller movements on both sides. We also need to take into consideration that we all have a dominant side in normal movement that is easier to control. Evidence suggests the dominant side is worse in PD, perhaps due to brain asymmetry, meaning anything involving that side is most likely going to be slower and more uncoordinated, such as balancing on your dominant side or having to pivot on your dominant foot (1,2). Again, comparing it to a car running, if you have a bad steering wheel, your turns are going to be a little rough and you might end up swerving more or less on target. Or you need new adjustments or wheel bearings that make your balance and steadiness just a little bit better (speaking from personal experience). These parts make a car drive smoothly, as the neural circuits involved in the basal ganglia — along with all the new motor regions I mentioned–interact as one unit to make the walking as coordinated as possible.

This type of movement is also affected by our favorite neurotransmitter: dopamine. As we know, dopamine affects the basal ganglia, which has a conversation with all of the different areas we’ve talked about, such as the supplementary motor area, which is important for coordinating movements. We have seen in past research that taking dopaminergic medication has positively affected Phase Coordination Index (PCI), which measures bilateral coordination by looking at footsteps and foot switching (4). What does this mean exactly? Taking dopaminergic medications creates a more balanced movement, most likely by increasing basal ganglia activity, which thus increases the conversation between this and other movement areas needed for bilateral movement.

We also know that exercise is great for PD! Not only has this been seen in PD-specific fitness classes, but in research as well! Taking medications that increase dopamine uptake can mitigate some of these falters in movement and can create a more efficient signaling cascade, but it can only do so much. The other part of strengthening these pathways comes from exercise that can lead to better balance, smoother motion, and greater bilateral coordination! We’ve seen in some research studies on physical therapy techniques that auditory and visual cues, premeditated/thoughtful movements, and most importantly repeated balance drills can decrease FOG episodes, which could be attributed to a lack of bilateral coordination (3).

And what incorporates all of those? Exercise classes! In Part 2, we discuss Steps To Incorporating Bilateral Coordination Into Your Exercise Program.

Become a Parkinson’s Disease Fitness Specialist!

Check out Colleen’s online course on MedFit Classroom….

Co-Written by Colleen Bridges, M.Ed, NSCA-CPT and Renee Rouleau.

Colleen Bridges is the author of MedFit Classroom’s Parkinson’s Disease Fitness Specialist course. Renee Rouleau is a PhD student at the Jacobs School of Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo.

References

- van der Hoorn, A., Bartels, A. L., Leenders, K. L., & de Jong, B. M. (2011). Handedness and dominant side of symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 17(1), 58-60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.10.002

- Plotnik, M., & Hausdorff, J. M.. (2008). The role of gait rhythmicity and bilateral coordination of stepping in the pathophysiology of freezing of gait in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders, 23(S2), S444–S450. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.21984

- Rutz, D. G., & Benninger, D. H.. (2020). Physical Therapy for Freezing of Gait and Gait Impairments in Parkinson Disease: A Systematic Review. PM&R, 12(11), 1140–1156. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12337

- Son, M., Han, S. H., Lyoo, C. H., Lim, J. A., Jeon, J., Hong, K.-B., & Park, H.. (2021). The effect of levodopa on bilateral coordination and gait asymmetry in Parkinson’s disease using inertial sensor. Npj Parkinson’s Disease, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-021-00186-7

- Kramer P., & Hinojosa, J., (2010). Frames of Reference for Pediatric Occupational Therapy: 3rd Edition. Baltimore, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

- Magalhães, L.C., Koomar, J.A., Cermal, S.A. (1989, July) Bilateral Motor Coordination in 5- to 9-year old children: a pilot study. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. Volume 43 Number 7.

- Piek, J.P., Dyck, M.J., Nieman, A., Anderson, M., Hay, D., Smith, L.M., McCoy, M., Hallmayer, J., (2003) The relationship between motor coordination, executive functioning and attention in school-aged children. Archives of clinical neuropsychology. Elsevier’s Ltd. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2003.12.007

- Roeber, B.J., Gunnar, M.R. and Pollak, S.D. (2014), Early deprivation impairs the development of balance and bilateral coordination. Dev Psychobiol, 56: 1110-1118. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.21159

- Rutkowska, I., Lieberman, L. J., Bednarczuk, G., Molik, B., Kaźmierska-Kowalewska, K., Marszałek, J., & Gómez-Ruano, M.-Á. (2016). Bilateral Coordination of Children who are Blind. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 122(2), 595–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031512516636527

- Schmidt, M., Egger, F., & Conzelmann, A. (2015). Delayed Positive Effects of an Acute Bout of Coordinative Exercise on Children’s Attention. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 121(2), 431–446. https://doi.org/10.2466/22.06.PMS.121c22x1

- Tseng, Y., & Scholz, J. P. (2005). Unilateral vs. bilateral coordination of circle-drawing tasks. Acta Psychologica, 120(2), 172-198.