Can’t Vs. Doesn’t Understand; Coaching Towards Learning Style

“Okay, now let’s see a squat, I’m gonna go first and then you try.”

The above is a standard sentence during my PAC Profile assessments and it carries with it powerful proactivity. I just also serendipitously learned that “proactivity” is a real, bona-fide word. When we teach movement, it makes sense to demonstrate first. Explaining to anybody a physical activity they’ve never performed, or performed with questionable technique, will skew towards wheels-fall-off territory early. Proactive practices give us and our athletes more opportunity sooner, and reduce the need to backtrack.

The above is a standard sentence during my PAC Profile assessments and it carries with it powerful proactivity. I just also serendipitously learned that “proactivity” is a real, bona-fide word. When we teach movement, it makes sense to demonstrate first. Explaining to anybody a physical activity they’ve never performed, or performed with questionable technique, will skew towards wheels-fall-off territory early. Proactive practices give us and our athletes more opportunity sooner, and reduce the need to backtrack.

The most efficient use of initial instruction time (the first time we are teaching an exercise) looks like this:

- Label

- Demonstrate

- Provide supported performance

For the ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) population, labeling in particular can have interim or long-term benefit for language (productive and receptive), memory, and independence. If the athlete is familiar with the word “squat” and can equate it to the movement pattern that constitutes a squat (whatever their current ability level), the coach does not have to repeat and demonstrate and repeat and repeat and repeat. Because the athlete already knows. The word squat and the movement squat have been paired in a way that makes sense, and is memorable, for the athlete.

Labeling adds to the lexicon. It’s remarkable just how much functional language we can build through fitness programs. Not only exercise names “squat, press, pull-down, push throw, rope swings…” but objects “Sandbell, rope, cones, Dynamax ball, sandbag…” and abstract concepts including prepositions “in, on, under, right, left, up, down…” When our athletes are actively engaged in fitness activities teaching these terms/concepts is easily presented in a natural manner.

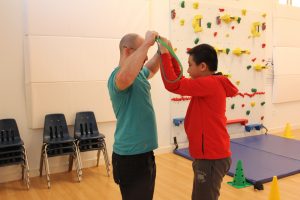

Demonstrating is crucial because it circumvents us and our athlete standing there and staring at one another (or off into the distance for those of our less-eye-contact-inclined friends). We always demonstrate a new exercise; this provides context and a framework for both the learning style and that athlete’s interpretation of what we just did. We’ll learn how they follow visual modeling and, often, how motivated they are to perform the thing they just saw.

Do they get right down to squatting? Are they hesitating? Overwhelmed? We will be given really good clues here.

Providing supported performance means that we are starting the athlete at a level of performance that they are sure to master quickly (if we have to progress the exercise immediately this is a good sign). If we wind up progressing an exercise five times during the first session then good. Good! This translates to the athlete having early successes that can be reinforced. We usually prefer to do the exercises that we’re good at, and our athletes with autism are not much of an exception.

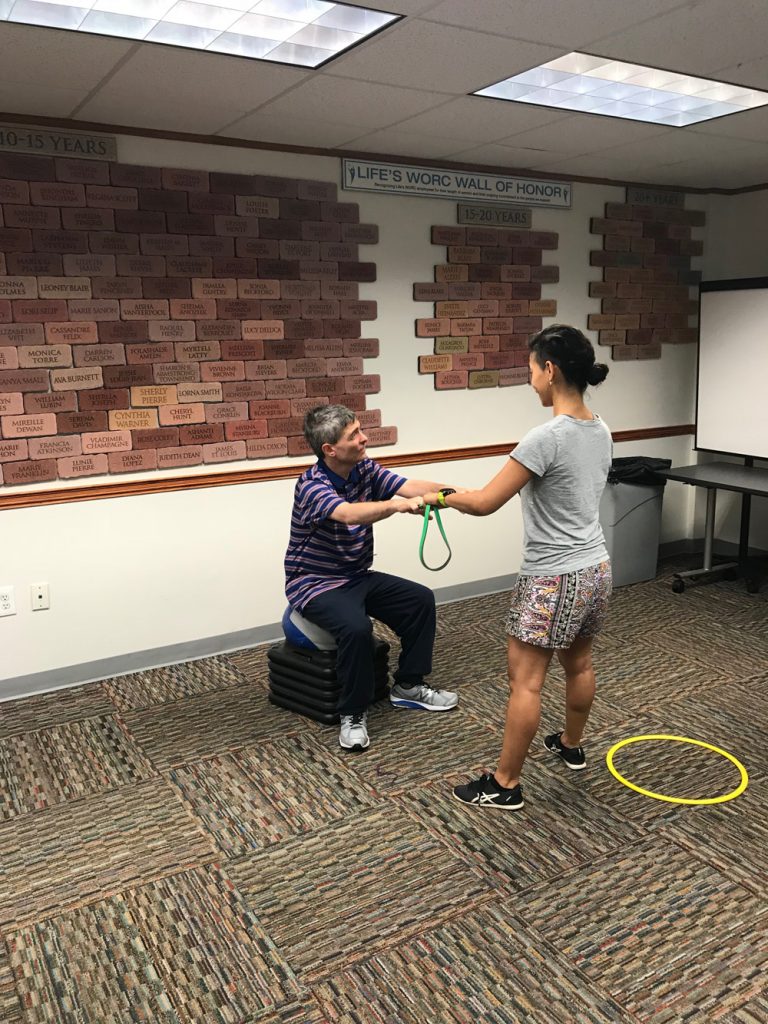

We may provide a physical or guided prompt early on with an exercise to ensure safe and effective technical performance. With the squat this may mean having the athlete hold on to a resistance band attached to a secure, stable area and squatting to an elevated surface (we always use Dynamax balls propped up on cardio step risers).

Depending on physical, adaptive, and/or cognitive ability, we may be able to fade this support in the first session or it could take months. I have some highly motivated athletes who, because of their physical needs, require longer practice with a given level of an exercise before they’ve reached mastery and can progress. The athlete should be held to the expectation of his/her best current level of performance (unless we’re talking about exceptional amounts of strength or power, because then programming changes a bit).

Efficient and effective coaching enables us to determine how best the athlete will learn a particular exercise. While it’s tempting to classify our athletes as “more visual” or “more kinesthetic” learners I’ve found that it is far better to approach this from an exercise-by-exercise basis. Some of my athletes need physical prompting through the end range of an overhead press but can “get” a band row when I demonstrate pulling my arms back while standing parallel to them.

Efficient and effective coaching enables us to determine how best the athlete will learn a particular exercise. While it’s tempting to classify our athletes as “more visual” or “more kinesthetic” learners I’ve found that it is far better to approach this from an exercise-by-exercise basis. Some of my athletes need physical prompting through the end range of an overhead press but can “get” a band row when I demonstrate pulling my arms back while standing parallel to them.

“Don’t know how” is a misinterpretation of breakdown in effective coaching communication. We need to be instructing with less words, more action. More show than tell.

When our athletes, or any of us, don’t understand the direction, the contingency, or the expectation we freeze, get off-task, get frustrated, or a Lucky Charms marshmallow cornucopia concoction of all three. Being proactive in coaching means giving our athletes the information they require delivered in a way that is useful.

It is easy to take for granted the neurotypical ability to interpret nuance, abstraction, and implied information; the untold stuff between the clearly marked things. Giving our athletes the context and environment to succeed, especially in the first few sessions or when teaching a new exercises becomes our bridge to success in coaching and performance.

Photos provided by Eric Chessen.

Eric Chessen, M.S., is an Exercise Physiologist with an extensive background in Applied Behavior Analysis. Eric provides on-site and distance consulting worldwide. He is the founder of Autism Fitness®, offering courses, tools, resources and a community network to empower support professionals to deliver adaptive fitness programming to anyone with developmental deficits to create powerful daily living outcomes that last a lifetime.

In the

In the  Focusing on a few exercises also gives our athletes the opportunity to learn the name and typical order in which the exercises can be performed. Whereas our warm-up/mobility section nearly always features hurdle steps, overhead resistance band walks, bear walks/crawls, and medicine ball throws (push, overhead, and scoop), our strength/focus section includes squats, presses, pulls, farmers walks, and heavy carries.

Focusing on a few exercises also gives our athletes the opportunity to learn the name and typical order in which the exercises can be performed. Whereas our warm-up/mobility section nearly always features hurdle steps, overhead resistance band walks, bear walks/crawls, and medicine ball throws (push, overhead, and scoop), our strength/focus section includes squats, presses, pulls, farmers walks, and heavy carries.

“Awesome. Yes, you can definitely do farmers carries right after this set of squats, okay?”

“Awesome. Yes, you can definitely do farmers carries right after this set of squats, okay?”