In order to design effective corrective exercise programs that both alleviate pain and improve function, fitness professionals must understand their clients’ strengths, limitations, and weaknesses.[1] This includes having an awareness of common structural imbalances such as leg length discrepancies (i.e., when one leg is shorter than the other). While it is not within a fitness professional’s scope of practice to diagnose a leg length discrepancy (LLD), it is extremely important that personal trainers and fitness instructors understand the ramifications of this imbalance and how it can affect a client’s musculoskeletal system.

Types and Prevalence of LLD

There are two types of leg length discrepancies: functional and anatomical. A functional leg length discrepancy refers to a musculoskeletal imbalance where any number of structures (or muscles) in the body are not working as they should. This results in parts of the skeleton being pulled out of alignment making it appear as though one leg is shorter than the other. Alternatively, an anatomical leg length discrepancy occurs when the bone(s) in one leg are actually shorter/longer than those in the other.[2] As the possible cause(s) of a functional leg length discrepancy are wide and varied, this article will focus on anatomical leg length discrepancies and how they affect your client’s body.

Anatomical, also known as true, leg length discrepancies have been found in as much as 95% of the population.[3] However, significant leg length discrepancies of more than one centimeter are found in about 1 out of 4 people.2 True leg length discrepancies affect the entire musculoskeletal system and play a substantial role in the health, function and experiences of pain for your clients.[4]

How LLDs Affect the Body

The body is designed to be dynamic and can adjust incredibly well to varying movements and positions. However, a true leg length discrepancy (that is left untreated) causes bones and joints to shift out of alignment, soft tissue structures like muscles, tendons, ligaments and fascia to compensate/overwork and can lead to pain and injury over time.[5] Some major areas of the body that are affected by a LLD discrepancy are the lower back, hips, feet and ankles.

LLD and the Lower Back

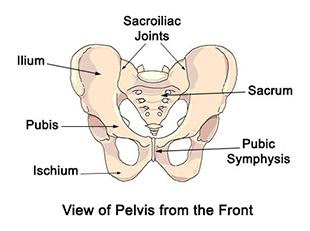

The pelvis forms the base of support for the spine. Therefore, a level and well-balanced pelvis is critical for spine health and optimal lower back function. In order to comprehend how an LLD can affect the spine and lower back, it is imperative to understand the structural anatomy of this area. Either side of the pelvis is made up of three bones (i.e., the ilium, ischium and pubis) that are fused together.[6] However, independent movement of each side of the pelvis is possible due to two important joints located in the pelvis. One of these joints is called the sacroiliac joint (SI joint). The SI joints are located on either side of the back of the pelvis where the top of the pelvis (i.e., the ilium) meets the base of the spine (i.e., the sacrum). The other joint is located on the front of the pelvis where the pubic bones (i.e., pubis) meet (i.e., the pubic symphysis) (see picture below).[6] Since the base of the spine articulates with each side of the pelvis via the sacroiliac joint, movement of the pelvis affects movement and function of the spine.

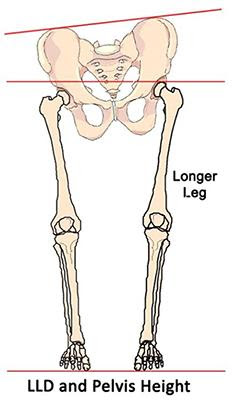

In addition to interacting with the spine, each side of the pelvis also articulates with the corresponding leg via the hip socket. From a skeletal point of view, the height of each side of the pelvis is governed, in part, by the length of the leg on that side of the body. If one leg is longer than the other then the pelvis will likely also be higher than that same side (see picture below).[2]

If the left side of the pelvis is higher due to a leg length discrepancy, then the base of the spine (i.e., the sacrum and coccyx) will shift toward that side also causing a compensatory shift in the rest of the spine all of the way up to the neck and head.[2] Therefore, a leg length discrepancy can cause pain and irritation to the joints of the pelvis, the intervertebral discs of the spine and the muscles and other soft tissues that help stabilize and mobilize these areas.

LLD and the Hips

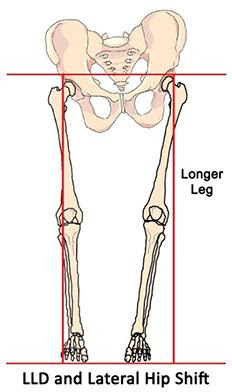

The relative length of each leg also affects the position and function of the hip socket. As one side of the pelvis elevates in compensation for a longer leg, the hip socket shifts laterally toward the longer side.[2] Consequently, the hip of the longer leg will shift to a position outside of the foot/leg (see picture below).

These compensation patterns in the hip/leg can cause various aliments for clients such as greater trochanteric bursitis, iliotibial band syndrome, tracking problems of the knee, and sacroiliac joint dysfunction.

LLD and the Feet/Ankles

Leg length discrepancies can also affect the function of the feet and ankles. Pronation, or a flattening out of the arch of the foot, is a common compensation for clients with an LLD to effectively shorten a longer leg by reducing the height of the arch. Conversely, supination effectively lengthens a shorter leg by increasing the height of the arch. As such, a common compensation pattern for someone who presents with a LLD is to overpronate on the side with the longer leg and over supinate on the shorter side. These imbalances in the feet typically display with compensatory shifts in the ankles as well. Overpronation is usually accompanied by an ankle that rotates in too much, while a supinated foot is accompanied by an ankle that rotates out too much.[5] These misalignment issues in the feet and ankles can lead to ankle sprains, Achilles tendinitis, plantar fasciitis, ankle impingement and a whole host of other painful problems.

How to Help a Client with a Suspected LLD

Being aware of the signs and symptoms of a suspected LLD will help you know when to make appropriate referrals to a licensed medical professional who can diagnose a client’s condition with the help of advanced imaging techniques (i.e., x-rays and CT scans). Developing a professional referral network that you can turn to for help with issues that fall out of your scope of practice allows you to provide a more comprehensive service for your clients. It also enables you to create long-lasting relationships with like-minded professionals who will act as a referral stream for your business.[7]

Once the appropriate referral and LLD diagnosis has been made, your allied medical professional will develop a treatment plan that may include a shoe lift. Your role, as an expert in muscles and movement, is to design corrective exercise strategies that help your client adapt to the shoe lift and the resultant new position of their head, neck, pelvis, spine, hips, feet and ankles. The golden rule of any exercise program – gradual progression – should govern every aspect of your client’s LLD treatment. Encourage clients to introduce their lift gradually when acclimatizing to their new leg length and follow the underlying doctrines of corrective exercise program design: utilize self-myofascial release strategies in the initial stages of adapting to the lift; progress to stretching and only conservatively add strengthening exercises after the client has had at least six months to a year to get used to their new leg length.

Justin Price is one of the world’s foremost experts in musculoskeletal assessment and corrective exercise and creator of The BioMechanics Method Corrective Exercise Specialist certification (TBMM-CES). The BioMechanics Method is the fitness industry’s highest-rated CES credential with trained professionals in over 70 countries. Justin is also the author of several books including The BioMechanics Method for Corrective Exercise academic textbook, a former IDEA Personal Trainer of the Year, and a subject matter expert for The American Council on Exercise, Human Kinetics, PTA Global, PTontheNET, TRX, BOSU, Arthritis Today, BBC, Discovery Health, Los Angeles Times, Men’s Health, MSNBC, New York Times, Newsweek, Time, Wall Street Journal, WebMD and Tennis Magazine.

References

- Bryant, C. X., & Green, D. J. (2010). ACE Personal trainer manual: The ultimate resource for fitness professionals (4th ed.). San Diego, CA: American Council on Exercise.

- Knutson, G. A. (2005, July 20). Anatomic and functional leg-length inequality: A review and recommendation for clinical decision-making. Part I, anatomic leg-length inequality: Prevalence, magnitude, effects and clinical significance. Chiropractic & Osteopathy, 13(11). doi:10.1186/1746-1340-13-11

- Pappas, A. M., & Nehme, A. E. (1979). Leg Length Discrepancy Associated with Hypertrophy. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, &NA;(144). doi:10.1097/00003086-197910000-00034

- McCarthy, J. J., MD, & MacEwen, G. D., MD. (2001). Management of Leg Length Inequality. Journal of the Southern Orthopaedic Association, 10(2). Retrieved July 01, 2016, from http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/423194

- Price, J. (2020). The BioMechanics Method Advanced Corrective Exercise Mentorship. The Biomechanics.

- Gray, H., Williams, P. L., & Bannister, L. H. (1995). Gray’s anatomy: The anatomical basis of medicine and surgery. New York: Churchill Livingstone.

- Price, J. (2018). The BioMechanics Method for Corrective Exercise. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.