As epidemic as postural imbalances are in the general public, the rate of postural abnormalities in the Parkinson’s Disease (PD) population are clinically diagnosed in one-third of cases.[1] This number is also quite likely very optimistic compared to practice. For the interest specifically of PD, postural concerns should be at the forefront of any physically rehabilitative program.

As epidemic as postural imbalances are in the general public, the rate of postural abnormalities in the Parkinson’s Disease (PD) population are clinically diagnosed in one-third of cases.[1] This number is also quite likely very optimistic compared to practice. For the interest specifically of PD, postural concerns should be at the forefront of any physically rehabilitative program.

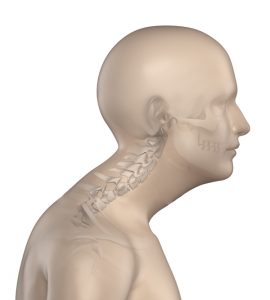

Why Is Cervical Posture So Important?

When the head is held forward, it alters the center of gravity. To compensate, the thoracic spine often grows overly kyphotic in an attempt to adjust the abnormal center of gravity. The lumbar is also impacted as it becomes excessively lordotic, all in an attempt to adjust for the initial issue with the neck position. This sets the stage for multiple discomforts and risks, including breathing difficulties, spinal injury, muscular weakness, headache, back and hip pain, and reduced diaphragmatic movement. Perhaps most pertinent to the Parkinson’s sufferer is the increased likelihood of that ever-present boogeyman: The Fall.

Approximately 60.5% of those with PD experience a fall in any given year.[2],[3] Those clients that do suffer a fall have a 39% recurrence rate. A separate study reported on the type and severity of injuries incurred by their PD patients, reporting that: “65.0% of them sustained an injury; 33.0% sustained a fracture; 75.5% of injuries required health care services; 40.6% of fractures required surgery…”[4] Correcting the cervical spine is the first step to correcting overall structural imbalances and helping to safeguard the PD sufferer from falls as well as numerous other physiological benefits.

A forward head posture, the result of a kyphotic cervical spine, can also impede the ability of the individual to breathe, interfering with both vital capacity and expiratory volume.[5] This same postural abnormality also contributes to spinal ischemia,[6] a risk factor and correlational aspect of numerous cognitive issues, including PD. The risk of falls and subsequent injuries, impairment on breathing, and impaired blood flow to the brain and spine all make postural correction an essential component of any PD-oriented wellness program. This makes the cervical spine the top priority.

How to Identify Cervical Kyphosis

The perfect answer here is to identify cervical kyphosis through radiography. This is rarely a tool for the physical trainer unless the diagnosis has already been made by a medical doctor. However, radiography is often times unnecessary except in a clinical setting as cervical kyphosis, as well as numerous other postural irregularities, is rather easy to identify through other means.

A casual glance of the individual at rest at standing can detail a great deal about the health or deterioration of cervical posture. The notorious “turtle” posture, where the forward head carry has tilted the entire cervical spine forward, is easily identifiable visually while the client is standing.

Alternatively, the trainer may have the client lay in a supine position and examine the tilt of the chin and position of the cervical spine. The chin pointed towards the ceiling helps identify a kyphotic condition.

There are also a number of tell-tale signs of irregular cervical positioning, namely pain throughout the neck and shoulders, instability, rigidity of the neck, and stiff sternocleidomastoids. A client who communicates these issues can be more supportive evidence of cervical kyphosis.

Plan A: Corrective Stretches & Strengthening

A large component of cervical kyphosis stems from both muscle weakness (elongation) and muscular stiffness (shortened). For the PD client, these issues are even more problematic since PD lends itself rather notoriously to muscular rigidity. It makes sense, then, that the first course of action is to elongate, or stretch, the shortened muscles. However, many trainers make the mistake of only addressing tonic muscles without also addressing the opposing weakness in other muscle groups. In this case, we are going to deal specifically with the sternocleidomastoids as our primary rigid muscles to address while we look to strengthen the levator scapulae, splenius cervicis, and trapezius muscles. Combining these two techniques can allow the trainer to assist the PD client in restoring muscular balance to the cervical spine, therefore improving cervical posture and setting the stage for future corrective work in the thoracic and lumbar region. As an added bonus, these improvements to the cervical spine will also help correct the consequences of cervical kyphosis mentioned earlier, principally ischemia and respiratory concerns.

Elongating (Stretching) The Sternocleidomastoids

The following stretches are very useful to targeting both the sternocleidomastoids and other muscles associated with neck flexion.

Movement 1: Thumb Chin Stretch

For all of the stretches that follow, have the client push his or her tongue to the roof of the mouth. This causes a slight variance in muscle recruitment deep into the throat and can improve the return on investment of this stretch. Also, always keep in mind appropriate breathing cues, especially in those with postural issues in the cervical and thoracic spine that has resulted in habitual shallow breathing.

Movement 1: Thumb-Chin Stretch

Perform this movement very carefully, slowly, and with no bouncing whatsoever. Take care to encourage deep, relaxed breathing. The throat musculature will activate with the appropriately deep breathing and, coupled with the tongue-to-palette technique discussed earlier, will help ensure a deep, comfortable stretch. My clients tend to enjoy this stretch as it makes their neck muscles feel released and fluid.

Movement 2: Rotary Stretch

Movement 2: Rotary Stretch

This stretch more deeply targets the sternocleidomastoids. Once the client is comfortable and proficient with both stretches, the trainer may opt for them to perform both stretches simultaneously.

This stretch should still be performed with the tongue pressed into the roof of the mouth. The most imperative aspect to this movement is the careful use of angles; it is not a simple turning of the head, but an approximate forty-five degree turn. With this movement, the client will find some empowerment since he or she, by feel, will be the best judge as to the most effective angle to use. Encourage he or she to relax into the stretch.

Movement 3: Supine Head Drags

As discouraging as the name might be, the movement itself is very basic and is a fantastic starting point alongside corrective stretching. This movement begins to rebuild weakened muscles deep around and surrounding the neck that may have atrophies to the point of uselessness.

With the head resting comfortably on a pillow or other soft surface, the client simply drags the head gently back and forth, both pushing and pulling with the neck muscles. This movement, along with corrective stretches, should form the main bulk of beginning training until full range of motion and confidence in neck stability is achieved.

Movement 4: Supine Chin-Tucks, Static

Movement 4: Supine Chin-Tucks, Static

While lying in a supine position with the head rested on something slightly lower than the rest of the body, the client tucks the chin and brings the back of the head off of the resting surface. The head should be kept in this elevated position for as long as the client is comfortable and only in the total absence of pain.

Movement 5: Supine Chin-Tucks, Dynamic

This movement is executed identically to Movement 5 but with the addition of repetition. Smooth movement, slow speed, and total control is essential.

Movement 6: Supine Deep-Breathing

Although listed as the last movement in this series, this is acceptable for any level of readiness. The client lays down with the shoulders in contact with the floor, the hands held supinated, and the chin gently tucked so that the cervical spine adopts its natural lordosis. With deep breathing in through the nose and out through the mouth, the client will often find a gentle and welcome stretch. Time maintained in this position also reinforces the communication between the mind so that the neck musculature can begin to relearn natural positioning.

Final Thoughts

Although in this series I address each region of the spine separately, it is imperative to understand that the spine acts as a single unit. In many cases, kyphosis of the cervical spine may be due simply to a kyphotic thoracic spine. This becomes even more likely when one considers the role of the scapulae in thoracic and cervical posture. Given the integrative nature of the spine, addressing only a portion in an attempt at corrective action is very likely to end in failure. A proper program will also include the other spinal regions and will be addressed, in turn, in the next two articles.

In Part 2 we will discuss the thoracic spine in terms of both isolation and in conjunction with the cervical spine.

Remember patience and move slow. My PD clients progress at a rate that is less than one-third of other populations, special or not. Much inspiration and respect can be drawn from their determination. Small, incremental progressions are the key to injury-free improvements. See you in Part 2!

Shane Caraway uses his education, experience, and credentials as a certified personal trainer and nutritionist to help others recapture the primitive mystique, strength, and beauty that their body is capable of. His greatest pleasure comes from the successes of his clients, no matter how mundane or simple each small victory may be. Always in pursuit of various techniques, compounds, nutrients, herbs, and other means to help support the body against disease, Shane finds the challenge of combating chronic disease to be the pinnacle of his work, especially with diseases and conditions that otherwise cause clients to surrender.

References

[1]http://www.parkinsonnet.nl/media/1004438/doherty_lancet%20neurology%20(2011)%20postural%20deformities.pdf

[2]http://www.pdf.org/en/science_news/release/pr_1373317337

[3]https://www.hindawi.com/journals/pd/2013/906274/

[4]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15580552

[5]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4755989/

[6]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3145857/