The “Dark Side” of Parkinson’s Disease: Why Parkinson’s Changed The Way We See, Part 1

The dark side of the moon is not considered a particularly exciting topic unless you are an astronomer or a Pink Floyd fan. However, the dark side of the moon exists and is just as important as the front of it.

So, what are the conditions of the dark side of the moon? Does it ever see the light of the sun? Why is it called the dark side? These are interesting questions with answers that I will leave to space experts, BUT what I will say is that the moon is similar to Parkinson’s Disease (PD). Yes, you read that correctly — the moon and Parkinson’s Disease are similar.

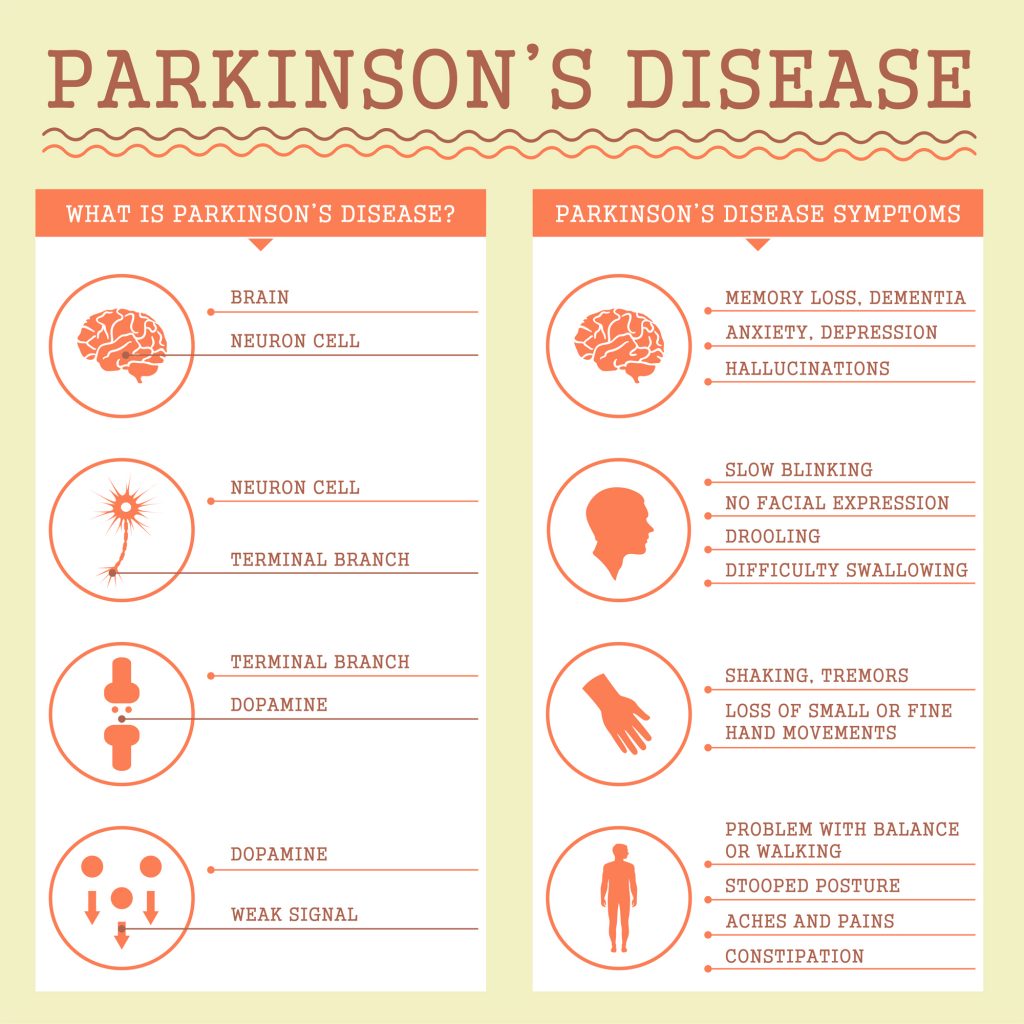

Parkinson’s Disease is most often characterized by a tremor and/or gait issues. Just as the moon has a dark side, unseen but present, Parkinson’s Disease has a “dark side”. As a fitness professional, understanding the “dark side” of Parkinson’s Disease and how it affects your “fighters” will enhance your program design skills, increase your confidence when counseling a “fighter” or care-partner and help build your relationship with other medical and fitness professionals.

The goal of this article series is to shed light on the “dark side” of PD. By incorporating the knowledge of medical professionals on my Bridges For Parkinson’s team, you will learn about research discoveries, resources for program design, useful tools for “fighters” and care-partners and ultimately, hope!

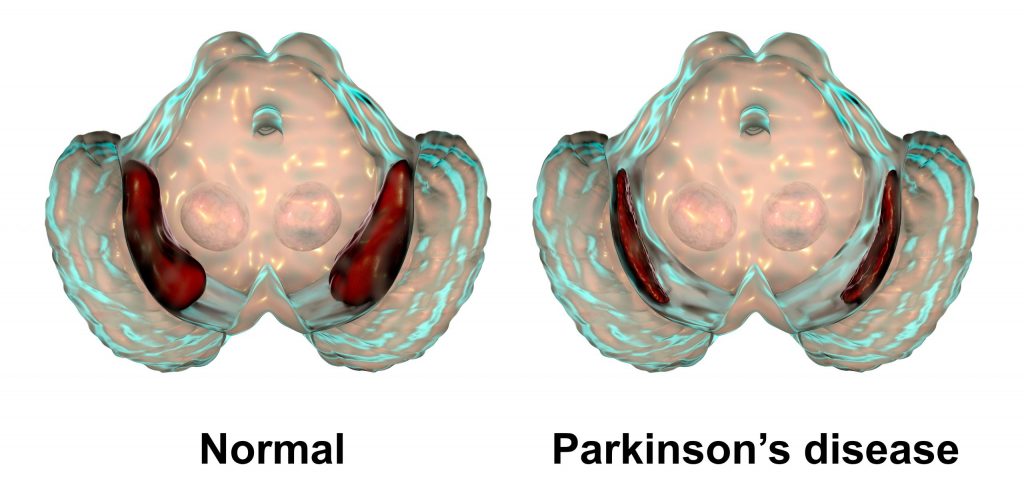

Vision impairments in those with PD is our first topic in this series. People living with Parkinson’s Disease experience changes in their vision as they age. These changes may include cataracts, macular degeneration, dry eyes, floaters, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, detached retina, trichiasis, and blepharitis. NOW, People living with PD may experience one or several of these issues due to normal aging. However, due to the depletion of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra, those with PD may also experience the following vision issues and/or impairments.

- Blepharospasm: uncontrollable eye twitching

- Blepharitis: Lack of blinking. On average, we blink 12-14x per minute. A person with PD may only blink 3-5x per minute. The result is inflammation on the edge of the eyelid. Eyelids may become irritated or itchy and appear greasy or crusty.

- Apraxia: “oculomotor apraxia” – the absence of or defect in voluntary eye movement. This may result in trouble initiating movement and moving the eyes in a desired direction

- Diplopia (Double Vision): when a single object becomes two objects.

- Dry Eyes: eyes may feel sandy or gritty.

- Blurry Vision: MAY be related to dopamine depletion in back of the eye and within the visual connections throughout the eye (Davis Phinney)

- Eye movement issues:

- Pursuit Movement: eyes are unable to work together to follow an object such as a plane flying across the sky.

- Saccadic Movement: unable to move eyes rapidly from one object to another such as completing a line in a book and going to the other side to the beginning of the next line.

- Vergence Movement: as the target or object draws closer to the person with PD, the eyes are unable to converge to maintain focus on the object causing double vision. Approximately 30% of people living with PD suffer from Vergence Eye Movement problems.

- Depth/Distance Perception

- Photophobia (also known as Light Sensitivity): may wear sunglasses indoors due to bright lights.

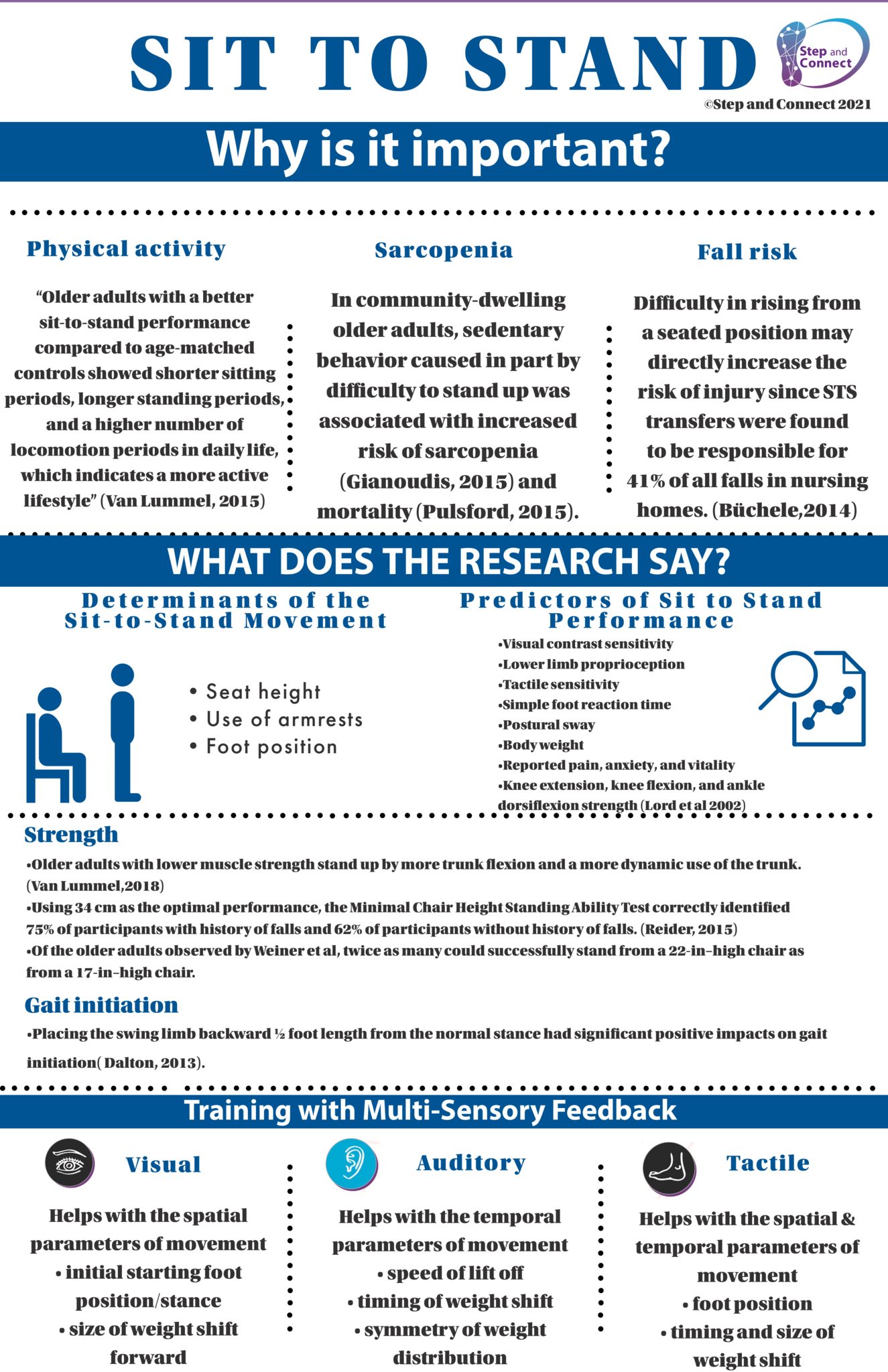

Fitness Professionals should inquire about vision impairments before a “fighter” begins an exercise program and obtain specific information about the vision impairment. Each symptom listed above can potentially compromise gait/balance, increase difficulty with Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and cause those with PD to isolate or become depressed due to lack of independence.

How We See

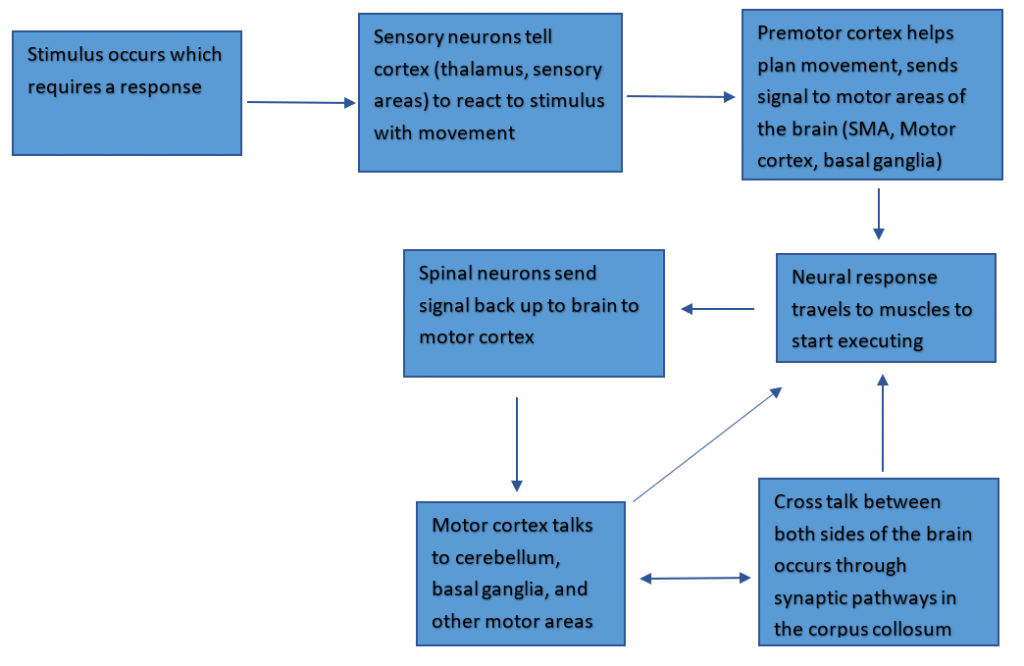

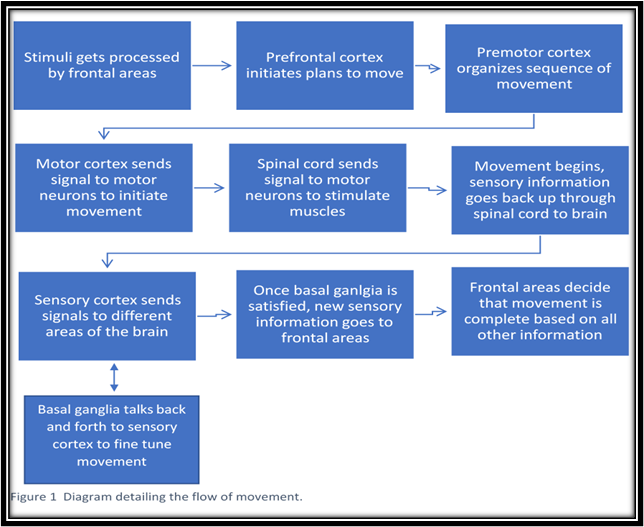

When we use our vision, we’re doing a lot of simultaneous tasks. We have to sense and process the stimuli, perceive and make sense of the stimuli in the context of the situation, and translate those signals into a response (i.e. movement, bringing up memories, emotions) to the initial stimuli.

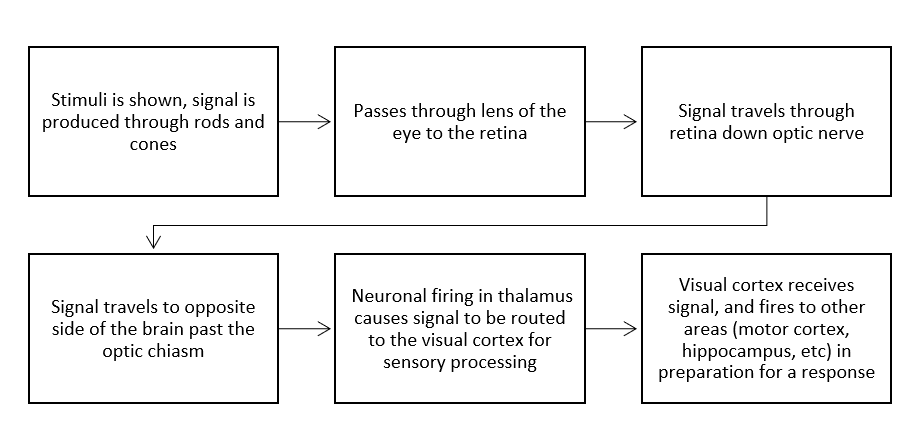

For example, a stimulus such as a car passing by causes numerous neurological responses to take place in the visual system. First, that stimulus passes through the lens into rod and cone cells that make up light/shadows and colors to put the image together, which then reaches axons in the retina that extend through the optic nerve. Once that signal travels through the optic nerve, it reaches the optic chiasm, where the stimulus passes over to the opposite side of the brain from the visual field and eye. Interestingly, this car is not visually processed right-side up! Instead, it goes into your brain upside-down as the eye lens flips the image. That image then travels through the thalamus (our “sensory relay system”), and to the primary visual cortex, where the image gets processed and relayed to other sensory systems to prepare for a response. The Role of Dopamine in the Eye

The Role of Dopamine in the Eye

You wouldn’t think that dopamine is involved in vision. We think of it relative to its impact on motor control and behavior reinforcement. However, even in ocular movement, lack of dopamine can impact a person with PD significantly, possibly resulting in apraxia. Dopamine also regulates light sensitivity in our retinas that helps to modulate our circadian rhythm, known as our “internal clock”. As dopamine decreases with disease progression, the sensitivity of the visual system decreases as well, hindering the ability to differentiate between light conditions such as day and night, potentially leading to other problems in circadian rhythm (Witkovsky, 2003). Over time, we see a loss of dopamine projections into the eye worsening vision such as blurry vision, light sensitivity, or even color vision deficiency as listed above. Unfortunately, there is not enough research on the involvement of dopamine in PD vision to give a clear-cut role of dopamine, but current research points to dopamine as a larger part of vision problems experienced by those with PD.

Physicians

It is crucial to understand the connection between the brain and PD vision related issues. Knowing when to refer a “fighter” to a vision specialist is critical to building your team of advisors and establishing a strong medical-fitness program in your community.

I highly recommend finding a neuro-ophthalmologist or a neuro-rehab optometrist to join your team. A neuro-ophthalmologist specializes in both fields of neurology and ophthalmology. They complete a residency in either neurology or ophthalmology then continue to complete a fellowship in the complementary field.

Dr. Jamie Ho, OD, FAAO, FCOVD of Nashville, TN is a member of my advisory board and she is a neuro-rehab optometrist. Dr. Ho addresses the functional deficits that result from the neurologic changes. You can learn more about Dr Ho’s practice at www.hovisiongroup.com.

To find a neuro-optometrist or neuro-ophthalmologist in your area go to www.noravisionrehab.org

Medication

Medication for PD certainly improves PD symptoms however, visual side-effects can occur.

For example, according to www.healio.com, Anticholinergic meds such as Artane are used to address tremors but can also cause dry or blurry vision. The Journal of Parkinson’s Disease notes that dopamine agonists cause hallucinations, Levodopa may lead to ocular dyskinesia (involuntary eye movements), and MAO inhibitors to blurry vision.

Fitness Professionals need to record all medications during the initial assessment and update any medication changes quarterly, at minimum

Click to read Part Two of this article, which offers some tips for fitness professionals working with PD clients with vision challenges.

Co-authored by Colleen Bridges, M. Ed, NSCA-CPT; Renee Rouleau-B.S., PhD student, Jacobs School of Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo; Kristi Ramsey, OTD, OTR/L.

Reviewed By: Dr. Jamie Ho, OD, FAAO, FCOVD

References

- Berliner JM, Kluger BM, Corcos DM, Pelak VS, Gisbert R, McRae C, Atkinson CC, Schenkman M (2018) Patient perceptions of visual, vestibular, and oculomotor deficits in people with Parkinson’s disease. Physiother Theory Pract. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2018.1492055 [PubMed].

- Borm, C., Smilowska, K., de Vries, N. M., Bloem, B. R., & Theelen, T. (2019). How I do it: The Neuro-Ophthalmological Assessment in Parkinson’s Disease. Journal of Parkinson’s disease, 9(2), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.3233/JPD-181523

- www.DavidPhinneyFoundation.org.

- Mayo Clinic, (2020)“Parkinson’s Disease Symptoms and Causes.” http://wwwmayoclinic.org20376055.

- Nowacka B, Lubinski W, Honczarenko K, Potemkowski A, Safranow K (2014) Ophthalmological features of Parkinson disease. Med Sci Monit 20, 2243–2249.

- Witkovsky, P. Dopamine and retinal function. Doc Ophthalmol 108, 17–39 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:DOOP.0000019487.88486.0a.

Contrary to popular belief, neurogenesis continuously occurs in the adult brain under the right conditions such as with exercise. Substantial benefits on cognitive test performance were noted for combined physical and cognitive activity than for each activity alone. It was also noted that the physical and cognitive exercise together might interact to induce larger functional benefits. “We assume, that physical exercise increases the potential for neurogenesis and synaptogenesis while cognitive exercise guides it to induce positive plastic change” (Bamidis, 2014). To maximize cognitive improvement, combine physical exercise with cognitive challenges in a rich sensorimotor environment that includes social interaction and a heaping dose of fun.

Contrary to popular belief, neurogenesis continuously occurs in the adult brain under the right conditions such as with exercise. Substantial benefits on cognitive test performance were noted for combined physical and cognitive activity than for each activity alone. It was also noted that the physical and cognitive exercise together might interact to induce larger functional benefits. “We assume, that physical exercise increases the potential for neurogenesis and synaptogenesis while cognitive exercise guides it to induce positive plastic change” (Bamidis, 2014). To maximize cognitive improvement, combine physical exercise with cognitive challenges in a rich sensorimotor environment that includes social interaction and a heaping dose of fun.