It all started over 40 years ago, when I chose as my sport – some would say, my life – the Korean martial art of Tae Kwon Do. I was young, fit, pretty strong and, unbeknownst to me, very flexible – perfect for the art of kicking high and hard. Once I got hooked on it, I was in the gym a few hours a day, 6-7 days a week…for the next almost 20 years. That did not include the running I did to get my cardiovascular conditioning primed for the art and sport I was practicing at high levels of both skill and competition. I knew then, at age 19, that I was going to pay for the training and abuse I was putting my body through, but not until I was older, say, 40 or so. In those days, joint replacements were very, very uncommon but it was not the joints I thought would take me down; I had this silly ‘premonition’ that I would die before they went bad enough to warrant that kind of repair.

Then, at the ripe age of 52, having a great workout with a client throwing medicine balls, standing on one leg at a time, catching with a hop and a twist, much to the reader’s consternation, nothing happened. No ACL tear, no low back twinge…nothing; nada; nil. I was fine and finished my day as a personal fitness trainer as usual. By then my Tae Kwon Do career had shifted to that of an instructor largely because of two prior knee arthroscopies to clean out the mess that had accumulated from all those pivots and jumps and kicks. I knew I had osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee and my orthopedic surgeon said I’d be getting a new knee within 5-10 years of the second surgery. I was now 5 years post-second surgery and was hurting but not too badly, just enough that running, jumping and kicking were forever in the past. Still in good shape – when you own a gym, that’s pretty easy…and expected – I could do most everything else I wanted. In fact, that same night, after tossing the med ball on one leg, I descended into the basement to ride my recumbent cycle. Those first few strokes, however, noticeably affected the inner thigh, the groin, of the leg that had had the knee surgeries. I must’ve tweaked my hip flexor, I thought. Subsequent days, however, proved more painful than I would have expected. Finally a physical therapist who saw clients at my gym checked me out and suggested I see a doctor and get X-rays. So, back to my knee doc I went, and he showed me some pretty severe hip OA that I had but never noticed until it flared up. (Note to others, ex-athletes and current athletes: OA happens, like other unpleasant expletives, even if you have not yet felt it.) After visiting with a hip doctor in hopes he could do an arthroscopic delay-tactic surgery, where I was told it would be a waste of time and money, I settled into the reality that someday I’d be getting a new hip. Eight years later, I finally got that new knee, too. And I feel and move great!

Then, at the ripe age of 52, having a great workout with a client throwing medicine balls, standing on one leg at a time, catching with a hop and a twist, much to the reader’s consternation, nothing happened. No ACL tear, no low back twinge…nothing; nada; nil. I was fine and finished my day as a personal fitness trainer as usual. By then my Tae Kwon Do career had shifted to that of an instructor largely because of two prior knee arthroscopies to clean out the mess that had accumulated from all those pivots and jumps and kicks. I knew I had osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee and my orthopedic surgeon said I’d be getting a new knee within 5-10 years of the second surgery. I was now 5 years post-second surgery and was hurting but not too badly, just enough that running, jumping and kicking were forever in the past. Still in good shape – when you own a gym, that’s pretty easy…and expected – I could do most everything else I wanted. In fact, that same night, after tossing the med ball on one leg, I descended into the basement to ride my recumbent cycle. Those first few strokes, however, noticeably affected the inner thigh, the groin, of the leg that had had the knee surgeries. I must’ve tweaked my hip flexor, I thought. Subsequent days, however, proved more painful than I would have expected. Finally a physical therapist who saw clients at my gym checked me out and suggested I see a doctor and get X-rays. So, back to my knee doc I went, and he showed me some pretty severe hip OA that I had but never noticed until it flared up. (Note to others, ex-athletes and current athletes: OA happens, like other unpleasant expletives, even if you have not yet felt it.) After visiting with a hip doctor in hopes he could do an arthroscopic delay-tactic surgery, where I was told it would be a waste of time and money, I settled into the reality that someday I’d be getting a new hip. Eight years later, I finally got that new knee, too. And I feel and move great!

What is Cartilage: How OA Happens?

Cartilage is a smooth, low-friction cushion made of proteoglycans (heavily-glycosolated (carbohydrate-connected) proteins) and collagen (of which there are many types). Unlike bone, it is softer, more pliant and, after a certain age, less capable of remodeling itself if damaged. Due to a lack of blood vessels, it gets its nutrients from the squeezing and pumping action of the bones on which it is attached. Thus, activity and movement are essentially good – no, they are essential – for healthy cartilage. However, over time, cartilage loses its ability to absorb fluid and gets, for lack of better words, dry and brittle. Add extra weight to it, such as with the weight-bearing joints (ankles, knees, hips and spine), and you get increased forces acting on less pliant tissue leading to little cracks and fissures in it. Now, add extra movements and suddenly chunks of cartilage are floating around in the joint space. Or injure it acutely and keep abusing it over time – as I did – and the damage accrues over time, too.

As we age, small cracks become bigger, and small chunks start acting like sandpaper over the remaining good areas of cartilage, and soon you have exposed parts of the bone with no protection against the forces acting on that joint. It’s just a matter of time before it’s so worn out that the space between the two bones is thinner, and bones start rubbing on each other creating osteophytes, or what most of us know as ‘spurs’. These spurs further wear out the cartilage on the adjacent bone and it’s not long before it hurts to move that joint. This is osteoarthritis (OA) which differs from rheumatoid (RA) and other forms of arthritis in that it is usually the result of injury, pathomechanics (bad alignment of the joint such that inappropriate wear occurs) and/or time and aging. RA and juvenile, as well as other types of arthritis, on the other hand, are autoimmune disorders, where the body attacks its own cartilage for as-yet unknown reasons. The problem, however, is not simply a bone-on-bone, cartilage-free joint. The consequent reduction in movement leads to loss of function, loss of muscle strength, increased fatty infiltration within the muscles around the joint, reduced fitness, reduced wellness (from a cardiovascular and metabolic standpoint) and, at some level, reduced quality of life. At some point, if you live long enough and prefer to have a quality of life beyond sitting in a chair, joint replacement, or arthroplasty, becomes an option. For simplicity, we will refer to total knee replacements as TKA and total hip replacements as THA.

Who Gets OA and Arthroplasty?

According to the Arthritis Foundation, over 50 million people in America are dealing with arthritis, most – up to two-thirds – being under 65 years of age; however, arthritis is very democratic with children as young as 6 months old to Baby Boomers not yet ready to get their first Social Security check suffering from it. (1) In fact, it is estimated that over 300,000 kids have arthritis. (1) Arthritis affects people of all races: “more than 36 million are Caucasians, more than 4.6 million are African-Americans and 2.9 million are Hispanic.” (1) About 27 million of the 50 million with arthritis have OA. (2) “People with arthritis account for 44 million outpatient visits and 992,100 hospitalizations. (2) It is estimated 67 million Americans will have arthritis by 2030. (2) According to a study in Canada, 10-15% of arthritis patients have OA due to prior injury which generally affects younger, more active people. (3)

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality says about 600,000 knee replacements are done each year in the US. (4) The American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons notes that most of these procedures are good for 10 – 20 years, with new technologies and surgical techniques being developed regularly so that people older and younger can benefit from them. (4) It is the purpose of the rest of this essay to discuss, not the surgical procedures or post-surgical therapies for those getting joint replacements, but the kinds of exercises one can do for oneself in addition to the basic therapies. In other words, the post-rehab exercises that will enhance both recovery from surgery as well as quality of life afterward.

Quick Review of Physical Therapy Goals

First and foremost, in addition to the ever-present prevention of infection which could severely hamper recovery and even lead to catastrophic consequences such as revision (corrective surgery) or death, doctors and therapists strive to get range of motion (ROM) restored. This is because of three things that have happened. First, the reduced ROM sufferers have developed as their disease progressed and movements were hampered. Second, after surgery, there is a tendency for muscles to contract to protect the joint as they don’t want to allow excessive movement at the joint. Finally, there is inflammation and the swelling around the joint causes tightness of the surrounding tissues, from the inner joint capsule to the skin, further hampering full motion.

Nowadays, patients are given drugs to reduce swelling so as to permit better motion, and to minimize pain, both surgical as well as during the imposed movements therapists encourage. These serve another purpose, however: by reducing inflammation, which shuts down nerve impulses to the muscles around the joint, they allow those muscles to be voluntarily (by conscious decision) to ‘fire’ so that they can start doing their jobs quickly. This reduces the typical post-surgery atrophy that would be mounted on top of the significant atrophy most OA sufferers have simply from lack of use. Thus, along with working to restore ROM, therapists encourage immediate use of these muscles as patients start along the road to full recovery. The sooner they are jump-started, the more likely full function will be restored. Hence, simple isometric contractions are encouraged for the quadriceps (quads = front thigh muscles), hamstrings (hams = back thigh muscles), and gluteals ((glutes = buttocks muscles), especially gluteus medius (glute med = the muscle on the side of the hip that pulls the thigh away from the other thigh sideways (abduction). These valiant efforts by the therapists come during the most fearful time for the patient, and when the patient is very likely to believe if not truly experience both pain and drug-related lethargy. But they are essential to rapid and full recovery.

When you start physical therapy (PT) outside the hospital, more aggressive measures will be implemented to restore ROM, especially for TKA; the hip has very good and very normal ROM immediately, if normal gait is all you seek. (Some athletic types, especially former dancers, martial artists, etc, may wish to resume some level of previous activity mandating higher ROMs. This should be cleared with the surgeon as there are typically restrictions given, to be followed for at least a few months while the capsule heals and in some cases for life, that warrant caution.) In order to achieve life-style related motion such as for sitting, the knee has to bend at least 90 degrees, although 120 is preferred. Therefore the quads need to be stretched. Since the post-surgical knee is swollen, this is challenging and requires some hearty efforts by both PT and patient. For the most part, after a THA, unless there is concomitant knee OA, this ROM is intact. However, with one major concern being subluxation or dislocation of the prosthetic hip, usually flexion beyond 90 degrees (bringing the thigh to perpendicular to the trunk) is not permitted; furthermore, doing so while also adducting the leg (crossing the midline) is also taboo.

As noted above, since THA rarely requires efforts to increase ROM, this part of the discussion will stick to TKA. In order for the quads to work efficiently, to straighten the leg, the hams have to be supple enough to allow the knee to extend fully. There are various methods to reinforce this capacity immediately post-surgery, from a passive movement machine to which your leg is strapped to a removable cast that does not let your knee flex even in your sleep (which it would love to do.) In therapy, though, all kinds of stretching techniques are applied to get the knee straight and inflammation and fear play into resistance to stretch for these muscles, too. As for hips/glutes, unless there is concomitant hip OA, normal range is intact in those with knee OA; however, normal function is not, but this takes us into the strengthening realm, below. Early in therapy, though, glute exercises such as ‘tightening your butt’, ‘squeezing your cheeks together’ or ‘pushing your heel into the bed’ are encouraged.

You can see that these early, post-surgical exercises are ones that can be done in the hospital or residential bed and should be done frequently throughout the day to ensure rapid recovery even as it could be weeks or even months before full recovery is noted. Of course, since ambulation – a fancy word for walking – is a primary goal for anyone wishing to live independently, the PTs will get you up and about, initially with a walker to ensure your safety, progressing to crutches, then to one crutch, then a cane or nothing if you have good control of your body such that you won’t fall. They will also work on getting you to think about how you walk, to engage your glute med (side hip muscle) so that your hip does not shift outward with each step you take on the surgical leg. This is more of an issue with THA patients but TKA patients, due to many years of limping, are also programmed wrong and need to re-program those muscles.

PT can go on as long as (1) your insurance covers it, (2) you are willing and able to afford it on your own or (3) you are released due to successful restoration of basic function. From this point on, you could stop doing all your exercises and lead a fairly normal though not vigorous lifestyle; or you could take the bull by the horns and proceed to the next section to learn what exercises to do on your own, at a gym or at home, with or without supervision, that apply to both TKA and THA patients.

Post-Rehab Quality of Life Enhancing Exercises

For simplicity, I will break down the exercises into four components, starting at the bottom: lower leg, quads, hams, glutes. Some basic guidelines apply:

- Find a safe environment to do the standing exercises so that you have something to prevent a fall such as a wall or kitchen counter to grab.

- Start all exercises with 1-3 sets of 10 repetitions, preferably every day but no less than 4 times a week.

- Progress first by adding 2-3 repetitions every 3-4 workouts. When you can do sets of 30, consider adding extra resistance as described for each exercise.

- Perform each exercise slowly in both directions – up and down, for example. You might also hold the tension point for a second or two before going back to the start position.

- Over time, to increase power – which you lost by not being able to exert while the joint was deteriorating – add either faster movements on the up or holding a weight, light at first but eventually increasing it as you get stronger.

- When ready to increase power by whichever method, decrease the repetitions/set to 10 again and progress to sets of 15. After a couple of weeks at 15 repetitions, if you are adding weighted resistance, start with sets of 8 and work your way to sets of 12. These repetition ranges, by the way, do not designate when you voluntarily stop even if you could do more; they are the number you can do with good technique before you start compensating.

- At some point, you will be considering resuming more active lifestyle activities. Consult with your surgeon to see if there are any restrictions, concerns or things to watch for so far as pains or injuries that may crop up. A certain amount of common sense is called for but a certain amount of early-training soreness is permissible. You should begin getting a sense of what is ‘good’ pain and what is ‘bad’ pain, with the latter requiring alterations in your exercise routine before you have to go back to see your doctor.

- If post-exercise soreness bothers you, ice the muscles or joint for 15-20 minutes every hour for a few hours within the first 24 hours. You can apply a heating pad on low heat before your next workout if you think it will help you warm up.

Lower Leg Exercises

The many years of altered gait, the limping pattern you’ve developed and the compensations throughout the system, leave weakness in their wake. One thing those who have OA do is put more work onto the good or better leg, especially when climbing steps or hills. Therefore, the calf muscles of the affected leg get weaker; not only do they lose strength, they lose propulsive thrust, or power. After surgery, as you re-learn how to walk, this is often an under-appreciated link in the chain. I highly recommend you initiate simple heel raises (pictured right), first off the floor while holding onto a kitchen counter or wall for stability, adding repetitions before adding anything to increase intensity. Having started with sets of 10 and progressing gradually to up to 30 repetitions, you can progress one of two ways: by doing them with your heels off the edge of a step or 2” x 4” so your heel goes below the ball of the foot, or by holding a weight – a dumbbell or even a jug of water. Regardless how you increase the challenge, proceed slowly to avoid injuring your Achilles tendon.

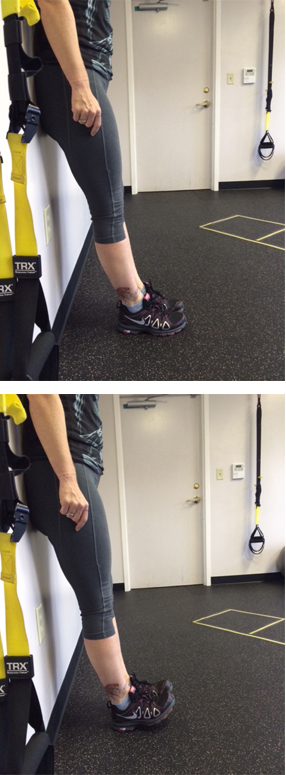

Anterior Shin Muscle

Perhaps you limped by turning your foot outward, or simply didn’t lift your leg up to walk properly. Either way,  the muscle on the front of the shin, which pull the toes and foot upward off the ground, have likely atrophied. For your future walking safety as well as a normal gait, doing anterior shin raises (pictured right) will help strengthen these muscles as well as actively stretch the calf muscles. I recommend doing simple wall exercises whereby you lean your back to the wall and move the feet about 8-10” from the wall. Then raise the toes and front of the foot off the floor as high as possible, hold, and let them return to the floor. You’ll be surprised at how difficult it is to raise them very high but if you continue doing these, both strength and flexibility of the ankle will increase and help you walk better and safer.

the muscle on the front of the shin, which pull the toes and foot upward off the ground, have likely atrophied. For your future walking safety as well as a normal gait, doing anterior shin raises (pictured right) will help strengthen these muscles as well as actively stretch the calf muscles. I recommend doing simple wall exercises whereby you lean your back to the wall and move the feet about 8-10” from the wall. Then raise the toes and front of the foot off the floor as high as possible, hold, and let them return to the floor. You’ll be surprised at how difficult it is to raise them very high but if you continue doing these, both strength and flexibility of the ankle will increase and help you walk better and safer.

Quads

You’ve probably been acquainted with variations of a squat, (pictured below) eithersit-stand from a chair or leaning on a wall or a large stability ball or simply in free space. Older, weaker patients may still be released from PT with admonitions to continue doing straight leg raises, without or with an ankle weight. But if you were squatting, hopefully your PTs have observed your technique to make sure your thigh does not turn inward. Continue this practice by squatting in front of a mirror. If you are not yet strong enough to feel secure  doing these in free space, do them near a wall to help with balance and with a chair – a firm, solid, stable chair – to aim at with your rear end. Even if you are still using a walker, gradually reduce your dependence on it to force the leg to do the work. Of course if the other leg is also afflicted, you may need to depend on the walker to assist the early rising or later sitting until that leg is stronger or gets its operation.

doing these in free space, do them near a wall to help with balance and with a chair – a firm, solid, stable chair – to aim at with your rear end. Even if you are still using a walker, gradually reduce your dependence on it to force the leg to do the work. Of course if the other leg is also afflicted, you may need to depend on the walker to assist the early rising or later sitting until that leg is stronger or gets its operation.

Another good quad exercise is the lunge. Again, be sure you are standing near a support structure – wall, counter top – in case you lose your balance as this movement depends more on the strength of just the front leg. It’s a very functional exercise and many variations exist. But the photos below will show you a nice variant that will help you perform more activities of daily living as well as prepare you for some sporting movements such as tennis and golf. Furthermore, as I’ve already alluded to, since it is more demanding from your inner stability mechanisms, start out with shallow movements and progress by going deeper over time. For those who’ve had a THA, the full depth lunge may be contraindicated for several months until your doctor approves flexing at the hips more than 90 degrees.

Another good quad exercise is the lunge. Again, be sure you are standing near a support structure – wall, counter top – in case you lose your balance as this movement depends more on the strength of just the front leg. It’s a very functional exercise and many variations exist. But the photos below will show you a nice variant that will help you perform more activities of daily living as well as prepare you for some sporting movements such as tennis and golf. Furthermore, as I’ve already alluded to, since it is more demanding from your inner stability mechanisms, start out with shallow movements and progress by going deeper over time. For those who’ve had a THA, the full depth lunge may be contraindicated for several months until your doctor approves flexing at the hips more than 90 degrees.

Step Ups

It’s been a while since you’ve been able to do these without pain, but now that you’ve had the surgery and PT, while there might be some residual tightness in the knee, for example, these are some of the toughest exercises to do. Whenever you get the option to climb steps, do so, holding onto the rail, even if you use a walking device like a cane. But if you have steps with a railing in your home, or if you are investing in a plastic multi-adjustable step that you might see in a gym, practicing stepping up frontward and sideways will really challenge the quads (and hams and glutes.) But also practice stepping down forward as if descending stairs. This may be very difficult at first and even somewhat painful for the TKA patient. A traditional step is 7.5” – 8.0” high. So the adjustable steps may be best as they start usually with a 4” step with 2” incremental platforms to add under the base. That forward step down, though, is quite demanding so starting with fewer repetitions or sets is probably well warranted.

It’s been a while since you’ve been able to do these without pain, but now that you’ve had the surgery and PT, while there might be some residual tightness in the knee, for example, these are some of the toughest exercises to do. Whenever you get the option to climb steps, do so, holding onto the rail, even if you use a walking device like a cane. But if you have steps with a railing in your home, or if you are investing in a plastic multi-adjustable step that you might see in a gym, practicing stepping up frontward and sideways will really challenge the quads (and hams and glutes.) But also practice stepping down forward as if descending stairs. This may be very difficult at first and even somewhat painful for the TKA patient. A traditional step is 7.5” – 8.0” high. So the adjustable steps may be best as they start usually with a 4” step with 2” incremental platforms to add under the base. That forward step down, though, is quite demanding so starting with fewer repetitions or sets is probably well warranted.

Hams

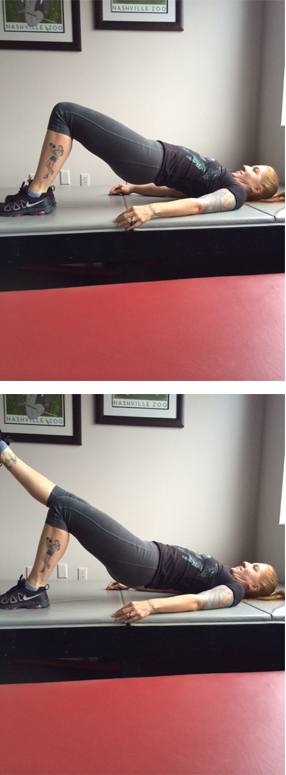

There are three very good exercises for the hams and they all get the glutes, too. First, and easiest, is the supine bridge (pictured right), something you likely did in PT. Now that you’ve been released, though, consider doing one leg bridges, with the other leg bent or straight. But there are two very important elements to consider. First, that you raise both hips equally and simultaneously and don’t let the suspended hip droop sideward. Second, beware the first few repetitions – sometimes the hams cramp up and, like a charley horse, grab your attention. Nothing dangerous but I thought I’d warn you.

Second exercise is the squat or lunge. But the hams don’t do much work until you’ve flexed at the hips almost 90 degrees which means you’re bending the knees pretty far, too.

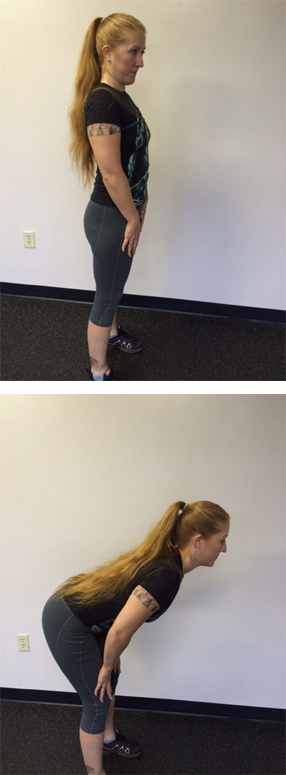

Third, and most challenging for those who’ve never lifted weights or who have very weak core muscles, is the Romanian dead lift (pictured left). A perfect lifting pattern is highly recommended for back safety but even if you can’t hold a perfectly neutral straight spine, you can always do the following basics. Stand with feet about hip width apart pointing forward. Head and chest held high with the shoulders pulled back so you’re standing ‘at attention’. Hands are on the front of your thighs. Now, bend from the hips, not the back, so the hands slide down the thigh to mid- or even lower- thigh. Be sure you keep your head, and eyes, on the wall in front of you. Raise the upper body keeping the hands on the thigh. The lower you go, the more hams you get, and even glutes…and even back muscles. But, as you consider progressions, first is reps, then depth and finally add load by holding a weight in both hands.

Third, and most challenging for those who’ve never lifted weights or who have very weak core muscles, is the Romanian dead lift (pictured left). A perfect lifting pattern is highly recommended for back safety but even if you can’t hold a perfectly neutral straight spine, you can always do the following basics. Stand with feet about hip width apart pointing forward. Head and chest held high with the shoulders pulled back so you’re standing ‘at attention’. Hands are on the front of your thighs. Now, bend from the hips, not the back, so the hands slide down the thigh to mid- or even lower- thigh. Be sure you keep your head, and eyes, on the wall in front of you. Raise the upper body keeping the hands on the thigh. The lower you go, the more hams you get, and even glutes…and even back muscles. But, as you consider progressions, first is reps, then depth and finally add load by holding a weight in both hands.

Glutes

We’ve gotten the glutes with squats, lunges, bridges and even dead lifts but some very basic and on-going side leg raises and clam shells (pictured right) should be part of your first year’s program. The height of the movements are not that important so long as you do not rotate the trunk so your body faces toward the ceiling; it should always be perpendicular to the floor or bed. Before adding resistance, however, I would recommend adding hold times up to 5 seconds. These are not muscles you need to get strong so much as they need to have endurance and control, so you may never add weight on these two exercises, just time under tension.

Conclusions

There are many things you should consider about these exercises and others even before your planned surgery. One study has shown that doing pre-hab for 4-8 weeks before TKA improves post-surgery leg strength and functional task performance such as sit to stand. (5) Also, another study has shown that adding a regimen of closed-chain exercises such as squats, lunges, step ups prior to surgery, which would enhance strength of the non-surgical leg, also helped recovery of function after surgery. (6) And another study found, in regard to athletes who get an ACL injury, that pre-surgical fitness is a good predictor of post-surgical sense of satisfaction, so maybe this reflects on joint replacement surgeries, too. (7) “Preoperative activity levels, age, male gender and lower body mass index (BMI) were predictors of higher activity level at one and five years following total hip replacement surgery.” (7) Something that I did before my TKA was to follow the advice of an University of Oregon study of essential amino acid supplements a week before and two weeks after surgery which showed nearly one-third of quad atrophy six weeks post-surgery compared to patients who did not take the supplements. (8)

As you proceed with your post-surgery, post-PT exercise routine, keep in mind that magic bullets rarely come without side effects. One study found that a post-rehab cohort doing an unsupervised exercise routine for 24 weeks, compared to a group that self-applied a placebo gel three times a week, had “roughly the same 13 and 36 week” patient outcomes. In fact the treatment group reported having more adverse events, although they were “relatively mild”. (9) This is just to say that if you are new to the exercises posted above, please consider engaging the services of a professional – a PT, an athletic trainer (AT), or a certified personal trainer (CPT) – to get you started properly to avoid, or at least minimize, your risk of injury and to optimize your chances for a more successful, functional and active lifestyle after your replacement surgery. This way, you can start a new way of living without chronic pain and disability.

Dr. Irv Rubenstein graduated Vanderbilt-Peabody in 1988 with a PhD in exercise science, having already co-founded STEPS Fitness, Inc. two years earlier — Tennessee’s first personal fitness training center. One of his goals was to foster the evolution of the then-fledgling field of personal training into a viable and mature profession, and has done so over the past 3 decades, teaching trainers across through country. As a writer and speaker, Dr. Irv has earned a national reputation as one who can answer the hard questions about exercise and fitness – not just the “how” but the “why”.

References

(1) http://www.arthritis.org/arthritis-facts/understanding-arthritis.php

(2) http://www.arthritistoday.org/about-arthritis/types-of-arthritis/osteoarthritis/what-you-need-to-know/osteoarthritis-is.php

(3) http://www.healthcanal.com/bones-muscles/56728-western-researchers-identify-potential-therapeutic-target-for-osteoarthritis.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+healthnewshc%2FOxfp+%28Health+News+from+HealthCanal.com%29

(4) http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/main.cfm(5) Swank, AM, Kachelman, JB, Bibeau, W, Quesada, PM, Nyland, J, Malkani, A, and Topp, RV. Prehabilitation before total knee arthroplasty increases strength and function in older adults with severe osteoarthritis. J Strength Cond Res 25(2): 318-325, 2011

(6) Brown, K, Kachelman, J, Topp, R, Quesada, PM, Nyland, J, Malkani, A, and Swank, AM. Predictors of functional task performance among patients scheduled for total knee arthroplasty. J Strength Cond Res 23(2): 436-443, 2009

(7) http://www.healthcanal.com/bones-muscles/53349-activity-level-may-predict-orthopaedic-outcomes-especially-in-younger-more-athletic-patients.html

(8) http://www.healthcanal.com/bones-muscles/44280-oregon-researchers-say-supplement-cuts-muscle-loss-in-knee-replacements.html

(9) http://www.healthcanal.com/bones-muscles/51064-questions-raised-about-physio-for-hip-osteoarthritis.html