Introduction

The foot is where movement begins, requiring mobility to perform simple functional movements. The knee however, requires stability with daily movements, but more importantly, dynamic sport movements such as soccer or football. In this article, we will review the anatomy of the knee, common injuries of the knee, functional assessments and training strategies to work with clients with previous injuries.

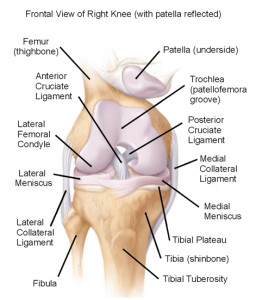

Basic anatomy of the knee

Let’s look at the anatomy of the knee.. The joint is vulnerable when it comes to injury, because of the mechanical demands placed upon it and the reliance for soft tissue to support the knee. There are two primary joints within the knee, the tibiofemoral joint and the patellofemoral joint.

Figure 2. Structures within the knee joint

Knee Joints

a. Tibiofemoral joint: Is a hinge joint that permits some rotation between the distal end of the femur and proximal end of tibia. The joint capsule surrounds the femoral condyles and tibial plateaus and provides stability to the knee by the medial collateral ligament(MCL) and the lateral collateral ligament (LCL).

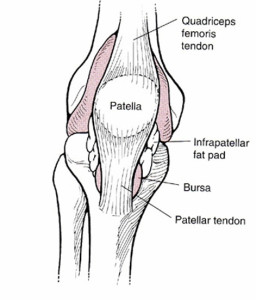

b. Patellofemoral joint: Is formed by the patella(knee bone) that glides in the trochlear groove of the femur. The height of the lateral femoral condyle helps prevent lateral subluxation, while soft tissue surrounds the joint to increase stability. This is seen in figure 3.

Figure 3. Patellofemoral joint

Primary structures within the knee joint: ligaments and mensici

Several ligaments described below provide stability at the knee joint.

a. Collateral ligaments: The two primary supporting ligaments are the medial collateral ligament (MCL), which is along the inside of the knee. The MCL is a thinner and weaker ligament biomechanically, making it more susceptible to injury more often injured per the research. While the lateral collateral ligament(LCL) is along the outside or lateral aspect of the knee providing lateral knee stability.

b. Anterior cruciate ligament(ACL): is the most commonly injured knee ligament and is taut during knee extension. It originates more proximally on the femoral side than the posterolateral (PL) bundle. It inserts anteromedially(front and to inner side) on the tibia. The ACL limits and controls forward translation of tibia on the femur and limits tibial rotation.

c. Menisci: the menisci are fibro cartilaginous discs located on the articular surface of the tibia along the medial and lateral tibial plateaus. The outer portion of the meniscus(lateral meniscus)is oval shaped (O) and thick. Attaching at the anterior and posterior horns via coronary ligaments.

Vascularity: The middle third and inner third of both menisci are relative avascular. The medial meniscus is more C-shaped, and thinner in structure. Both menisci receive nutrition through synovial diffusion and from blood supply to the horns of the menisci.

Function of the menisci: The menisci provide shock absorption, joint lubrication and stabilization.

Common injuries and causes

There are several common injuries that affect the knee. The most common are patella femoral syndrome(PFS), osteoarthritis(O.A.) and anterior cruciate ligament(ACL) injuries.

In this next section, we will review each condition providing a deeper understanding of each.

a. Patellofemoral syndrome

Pathophysiology/sign and symptoms: PFS is a condition where the patella does not translate biomechanically in the trochlear groove between the femoral condyles. Here the patella is positioned in either a tilt, glide or rotation accompanied by diffuse, achiness in the front of the knee.

Contributing Factors(Evidence Based Research): Several studies have shown that decreased flexibility of quadriceps and hip flexors(Lankhorst et al. 2012 & Meira et al. 2011) contribute to PFS. Decreased hip abductor strength has been shown a significant factor seen in multiple studies as contributing to PFS (Khayambashi, H., et al. 2012, Meira et al, (2011), Bolgla et al. (2008),Cichanowski et al. (2007), and Robinson et al. (2007).

Other factors include prolonged wearing of high heels, muscle imbalances(quadriceps>hamstrings).

b. Osteoarthritis(OA) of the knee

Figure 4. Osteoarthritis of knee

Pathophysiology/sign and symptoms: A degenerative process of varied etiology, which includes mechanical changes within the joint as seen in figure 4.

Risk Factors: Excessive weight born on hip joint, muscle imbalance, repetitive stressors.

Sign and symptoms: Pain in the a.m. described as “achy” that decreases as the day progresses, pain with weight bearing or walking, difficulty squatting, and lateral thigh discomfort.

c. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries

In the last several years, there has been more news about the incidence of ACL injuries. The incidence rate is greatest between the ages of 16 and 18 years. Female athletes are 3-9x more likely to sustain an ACL injury then male athletes. This results in at least 200,000 ACL reconstructions are performed each year in the United States, with estimated direct costs of $3 billion (in U.S. dollars) annually (Frobell, R., et al 2010).

Figure 5. Mechanism of injury for ACL tear

Pathophysiology/Mechanism of Injury: The knee is struck while in hyperextension, forcing tibia anterior(forward)on the femur, as seen in figure 5. The ACL can also be injured with same mechanism of injury with combined with medial rotation of the lower extremity(LE). This creates instability and a direct disconnect the nervous system to the musculoskeletal system because of the “lack of control” within the knee joint.

Common assessments

One great test to assess a client’s movement pattern, is the squat. The squat is a classic fundamental primal movement that someone typically performs almost on a daily basis. With this test, you can observe how the client’s ankle, knee, hip and back moves compared to normal movement patterns. This is seen in the figure below.

Figure 6. Squat in frontal and side view

Figure 7. In place lunge

Another simple assessment is an in place lunge, which examines one’s control through the entire kinematic chain. The lunge is another fundamental primal movement. The lunge is a dynamic movement that is typically performed during daily activities (stooping down to pick something up) or as part of an athletic movement.

This test examines ankle control, knee control and pelvic movement in the sagittal plane. Lastly, a diagonal traveling forward lunge looks at the ability of the client to control ankle, knee, hip, and pelvic movement in both the sagittal and frontal planes. This is not only a functional movement, but very effective for sport specific clients.

Training strategies and programming for knee injuries

Figure 8. Traveling forward lunge

With any injury, the most important thing to remember is the type of injury, healing time and prior level of function of the client.

a. Patellofemoral syndrome

Recommendations for training: Continued stretching of tight hip flexors, ITB, and hamstrings is fundamental. Client should be taught initially static core strengthening exercises, and then progressed to dynamic core strengthening as appropriate. Client would also benefit from education on shoes with respect to type that are most effective for them, and to cross train utilizing, such as hiking, yoga, pilates, and swimming. Lastly, to alter running surfaces(if client runs) and educating the client about changing their shoes every 500 miles or 6 months for maximum stability and control.

b. Osteoarthritis of knee (O.A.)

Recommendations for training: Aqua therapy has been shown in the research to significantly reduce pain, improved physical function, strength, and quality of life (Hinman, Rana S., et al 2007), stretching ITB, hip flexors, quadriceps and hamstrings, strengthening weaker hip abductors(glute medias/minimus). Strengthening specifically hip abductors in various studies when compared to general strengthening resulted in s significant reduction in knee pain, objective change in functional outcome tests, physical function and daily activities (Bennell,K.L., et al. 2010 & Hernández-Molina, G et al. 2008). Core strengthening shoulder also is an integral part of the training program.

Figure 9. Dynamic stabilization Training

c. ACL injury(Anterior cruciate ligament injury)

Recommendations for training: should focus on hamstring strengthening. Strengthening the hamstrings biomechancally transfers the load from the front of the knee to the back, thereby decreasing the stress to the ACL. Neuromuscular training as seen in figure 9, is very effective. It challenges the connection between the nervous and musculoskeletal system requiring the client to stabilize the entire kinematic chain. Research has shown neuromuscular training reduces ACL injuries (HUBSCHER, M. 2010 & Griffin LY, et al., 2006). Core strengthening should be multidirectional in nature as seen in figure 10.

Figure 10. Multidirectional

Training

In the picture on the left, left trunk rotation involves the internal/external obliques, atissimus withdorsi, and right glute medius and minimus muscles to stabilize, as the left glute medius and minimus to stabilize. With the yellow cord applied from the back, this engages the abs primarily to stabilize (from the front) accompanied by the obliques to stabilize, which the low back extensor muscles contract to prevent being pulled backwards. It is important to include dynamic training focusing on hamstrings, glute medius, maximus. Closed chain strengthening (CKC) exercises, such as diagonal forward and diagonal reverse lunges are not only functional, but replicate many common sports as soccer, football and basketball accordingly.

Contrainidications/Precautions: Avoid leg extension exercises completely this causes an anterior translation(shearing) of the tibia on the femur/stressing the graft. Therefore, the exercise is contraindicated. *Biomechanically, shearing stress on the ACL is greatest from 30 degrees of knee flexion to full extension.

Recommendations for training: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) Guidelines Post Therapy:

• Continuation of closed kinetic chain exercises(ie. reverse lunges, diagonal lunges,

forward lunge with medicine ball trunk rotation)

• 3 ½ months light jogging begins

• 4 months running begins

• 4 months introduction of plyometrics

• Surgical reconstruction typically sidelines athlete for 6-9 months and once cleared by physician can return to sport activities.

Summary

The knee is a dynamic joint that is comprised of a multitude of ligaments, tendons,

connective tissue, muscles that synergistically initiate and correct movement, and

stabilize when an unstable environment. Understanding the anatomy, biomechanics

and weak links of the knee, common injuries and evidenced based training strategies, should provide you with the insight to better understand and work with clients with these kind of injuries more confidently.

Written by Chris Gellert, PT, MMusc & Sportsphysio, MPT, CSCS, AMS.

Chris is the CEO of Pinnacle Training & Consulting Systems (PTCS). A continuing education company, that provides educational material in the forms of home study courses, live seminars, DVDs, webinars, articles and min books teaching in-depth, the foundation science, functional assessments and practical application behind Human Movement, that is evidenced based. Chris is both a dynamic physical therapist with 14 years experience, and a personal trainer with 17 years experience, with advanced training, has created over 10 courses, is an experienced international fitness presenter, writes for various websites and international publications, consults and teaches seminars on human movement. For more information, please visit www.pinnacle-tcs.com.

Chris is the CEO of Pinnacle Training & Consulting Systems (PTCS). A continuing education company, that provides educational material in the forms of home study courses, live seminars, DVDs, webinars, articles and min books teaching in-depth, the foundation science, functional assessments and practical application behind Human Movement, that is evidenced based. Chris is both a dynamic physical therapist with 14 years experience, and a personal trainer with 17 years experience, with advanced training, has created over 10 courses, is an experienced international fitness presenter, writes for various websites and international publications, consults and teaches seminars on human movement. For more information, please visit www.pinnacle-tcs.com.

REFERENCES

Bennell, K.L., et al., 2010, ‘Hip strengthening reduces symptoms but not knee load in people with medial knee osteoarthritis and varus malalignment: a randomized controlled trial,’ Journal of Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, vol. 18, issue 5, pp. 621-628.

Bolgla, L, et al., 2008, ‘Hip Strength and hip and knee kinematics during stair descent in females with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome,’ JOSPT, vol. 38, pp. 12-18.

Cicanowski, H et al., 2007, ‘Hip strength in collegiate female athletes with patellofemoral pain,’ Medicine Science Sports Exercise, vol. 39, pp. 1227-1232.

Frobell, R., et al 2010, ‘A Randomized Trial of Treatment for Acute Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears,’ New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 363, issue 4, pp. 331-341.

Griffin LY, et al., 2006, ‘Understanding and preventing noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injuries: a review of the Hunt Valley II Meeting, January 2005, American Journal Sports Medicine, vol. 234, pp. 1512-1532.

Hernández-Molina, G., et al., 2008, ‘Effect of therapeutic exercise for hip osteoarthritis pain: Results of a meta-analysis,’ Journal of Arthritis Care & Research, vol. 59, issue 9, pp. 1221–1228.

Hinman, Rana S., et al 2007, ‘ Aquatic Physical Therapy for Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: Results of a Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial,’ Journal of Physical Therapy, vol. 87, no. 1, pp. 32-43.

HU ̈ BSCHER, M., et al., 2010, ‘Neuromuscular Training for Sports Injury Prevention: A Systematic Review,’ American College of Sports Medicine, pp. 413-421.

Khayambashi, H., et al., 2012, ‘The Effects of Isolated Hip Abductor and External Rotator Muscle Strengthening on Pain, Health Status, and Hip Strength in Females With Patellofemoral Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial, ‘Journal of Orthopedic Physical Therapy, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 22-29.

Landry SC, et al., 2007, ‘Neuromuscular and lower limb biomechanical differences exist between male and female elite adolescent soccer players during an unanticipated side-cut maneuver,’ American Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 3, pp. 1888–1900.

Lankhorst, N, et al, 2012, ‘Risk Factors for Patellofemoral Syndrome: A Systematic Review,’ JOSPT, vol. 42, No. 2, pp. 81-90.

Meira, E., et al., 2011, ‘Influence of the Hip on Patients With Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome,’ Sports Health, vol. 3, issue 5, pp. 455–465.

Prins, 2009,’ Females with patellofemoral pain syndrome have weak hip muscles: a systematic review, Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, vol. 55, issue 1, pp. 9-15.

Robinsion, R et al., 2007, ‘Analysis of hip strength in females seeking physical therapy treatment for unilateral patellofemoral pain syndrome,’ JOSPT, vol. 37, pp. 232-238