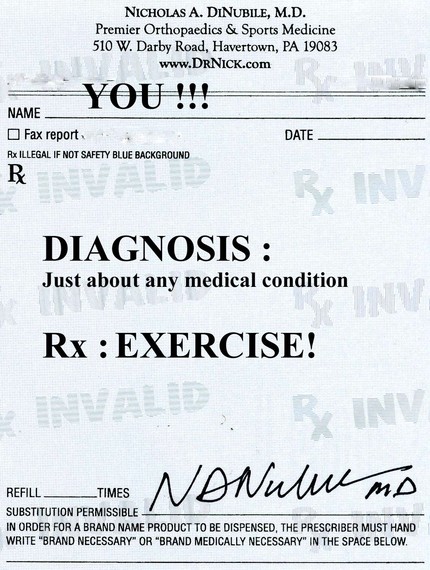

It’s been said: “If all the benefits of exercise could be placed in a single pill, it would be the most widely prescribed medication in the world.” Scientific evidence continues to mount supporting the numerous medicinal benefits of exercise. In fact, there’s hardly a disease that I can think of that exercise won’t help in one way or another, be it prevention, treatment, or even cure in some instances.

I have always had a passion for exercise since I received my first set of weights from Sears and a chin-up bar for my doorway at age 10. I was hooked. Over the years, I saw what it did to my outer body but never considered the deeper systemic effects. In four years of medical school, there was hardly a mention of exercise. My medical school, Temple University Med School, was considered quite progressive, and was one of only a handful of med schools in the U.S. that had a course, albeit short, on nutrition. But not a peep on exercise. Unfortunately, things are not much different now. When I was in my training to become an orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine, a medical journal, The Physician and Sportsmedicine, had a T-shirt that said “Exercise Is Medicine.” It struck a chord with me that changed the way I think about exercise, and those three simple words profoundly influenced my career and how I treat my patients. Interestingly, in recent years, the American College of Sports Medicine has started an “Exercise Is Medicine” initiative, and it’s been long overdue.

I have always had a passion for exercise since I received my first set of weights from Sears and a chin-up bar for my doorway at age 10. I was hooked. Over the years, I saw what it did to my outer body but never considered the deeper systemic effects. In four years of medical school, there was hardly a mention of exercise. My medical school, Temple University Med School, was considered quite progressive, and was one of only a handful of med schools in the U.S. that had a course, albeit short, on nutrition. But not a peep on exercise. Unfortunately, things are not much different now. When I was in my training to become an orthopedic surgeon specializing in sports medicine, a medical journal, The Physician and Sportsmedicine, had a T-shirt that said “Exercise Is Medicine.” It struck a chord with me that changed the way I think about exercise, and those three simple words profoundly influenced my career and how I treat my patients. Interestingly, in recent years, the American College of Sports Medicine has started an “Exercise Is Medicine” initiative, and it’s been long overdue.

I believe that exercise prescription should be part of the core curriculum in every medical and nursing school in the nation. We need to start thinking outside the pharmacologic or pill box. Every medical student takes a course in pharmacology. Thinking in pharmacologic terms and concepts, if you look up any drug in the PDR (Physician’s Desk Reference), or even in the Epocrates app, you will find in the discussion, for virtually every drug: its indications (what disease or diseases it’s used to treat); its dosage and dose-response curve (meaning the correct amount and range for optimal treatment, and the issues of over and under dosage); its half-life (a measure of the time it takes, once the drug is stopped, for its effects to wear off a certain amount, and eventually leave the body); and information on allergies, addiction and other potential complications . Well, I can do the very same for exercise!

So, with pharmacology AND exercise in mind, consider the following:

- Dorland’s Medical Dictionary defines medicine as “any drug or remedy.” So it really doesn’t have to be a pill to be a medicine.

- Like medications, regular exercise results in relatively predictable, highly specific changes in the human body. These adaptations occur both centrally and peripherally and include structural, hormonal, and biochemical changes. Different types of exercise will result in different results. Again, very specific.

- Exercise has been shown scientifically to be effective in the prevention and/or treatment of a wide variety of medical conditions, from cardiovascular disease and diabetes to arthritis, back pain and even certain mental health disorders and cancers. You can treat and prevent disease with it.

- There is an optimal dose and dose response curve for exercise depending on what you want to accomplish. And yes you can “overdose” (resulting in overuse injuries or overtraining syndromes which can result in structural and metabolic damage) and also “underdose” (where you really won’t enjoy the positive exercise effects you are seeking).

- Unfortunately, exercise has a half-life. Once you stop exercising, you begin to lose the multitude of positive benefits. And this happens relatively quickly, in weeks. Exercising earlier in life won’t help you later in life unless you continue. Exercise needs to be a lifetime habit, and it’s never too late to start.

- Believe it or not, some individuals are allergic to exercise! Exercise-induced asthma is common and some get hives from exercise (exercise-induced urticaria). There have even been rare reported cases of a severe allergic reaction called exercise-induced anaphylaxis. Fortunately, there are solutions for these issues, and they are no excuse to retire to the couch.

- There can even be addiction to exercise, and withdrawal type symptoms when certain individuals stop their exercise routines.

So, does exercise fit the bill as medicine? I certainly think so.

So why is exercise prescription not taught in every medical school in the nation? And more importantly, why do so few doctors prescribe exercise for their patience as a first-line intervention and/or cornerstone in the prevention and treatment of disease? At best, for many physicians, it’s an afterthought.

As health care is reformed in the United States, comprehensive strategies must be included to encourage more individuals of all ages to incorporate exercise into their daily routines, a cornerstone of personal health care reform. Nearly all people, including pregnant women, older people and people with chronic, degenerative, or handicapping conditions can benefit from a well-designed individualized exercise program. You are almost never too young, or too old, to start. Physicians and other healthcare professionals should play a critical role in this process. Years ago, I did a book for physicians to try to get them to think differently about exercise and get them to incorporate it in their everyday practice of medicine. In the forward to “The Exercise Prescription,” Arnold Schwarzenegger, then chairman of the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports, commented on his vision for health care providers in relation to exercise prescription. He wrote, “My hope is that each time physicians, regardless of their specialty, meet a patient, a category of treatment in their mental checklist is exercise, and a page of the prescription pad reflects this.” Even today, those words ring true, loud and clear.

I do believe the tide is changing with a new breed of younger, active physicians, but it is not happening fast enough. And I fear that with physicians under pressure to see more patients and spend less quality time with them, important preventive counseling will be the first to go. It takes time, and it’s really not reimbursed. I also believe that patients play an important role in bringing exercise into the physician’s office and into their black bag. Ask your doctor if exercise is right for you, specifically for your medical, orthopedic, neurologic, cardiac, metabolic or just about any other medical condition. And share this article with your physician and also those that you care about. Let’s restart the “Exercise Is Medicine” conversation and get everyone moving towards better health.

Originally published on the Huffington Post. Reprinted with permission from Dr. DiNubile.

Nicholas DiNubile, MD is an Orthopedic Surgeon, Sports Medicine Doc, Team Physician & Best Selling Author. He is dedicated to keeping you healthy in body, mind & spirit. Follow him MD on Twitter: twitter.com/drnickUSA