Exercise Solutions for Fibromyalgia

Approximately 4 million people in the United States live with fibromyalgia, an illness which manifests as severe muscle pain and chronic fatigue. Living with fibromyalgia — the cause of which is unknown, but seems to be connected to the nervous system — means coping on a daily basis with debilitating discomfort and a lack of energy, making exercise difficult. Indeed, a lot of different exercises can actually make the symptoms of fibromyalgia more acute, but there is a common misconception that exercise should be avoided completely by those with the condition.

Approximately 4 million people in the United States live with fibromyalgia, an illness which manifests as severe muscle pain and chronic fatigue. Living with fibromyalgia — the cause of which is unknown, but seems to be connected to the nervous system — means coping on a daily basis with debilitating discomfort and a lack of energy, making exercise difficult. Indeed, a lot of different exercises can actually make the symptoms of fibromyalgia more acute, but there is a common misconception that exercise should be avoided completely by those with the condition.

Giving up exercise is not the answer. Some forms of physical exercise may exacerbate pain, but this is due to the unsuitability of the exercise itself, rather than just doing exercise. In fact, performing exercises that don’t trigger symptoms can actually help, not the least of which is relieving mental and psychological fatigue which is connected to living with the illness.

Start slowly

Throwing yourself into a workout with no gradual build-up is not recommended for anybody, but least of all if you live with fibromyalgia. Intense workouts need to be increased over time, whether you’re 18 or 80, in good shape or not. Unprepared muscles will not respond well and it could take days to undo the damage caused. As little as 5 minutes spent walking can be the best approach.

“After a while, start to increase the amount of time you spend exercising bit by bit, but do not increase the rigorousness of the exercise, which will have a detrimental effect,” warns Pamela Chase, a Fibromyalgia expert at SimpleGrad and Revieweal.

Keep it low intensity

And with the case of fibromyalgia, high-intensity workouts should never be the aim. Pain will only be exacerbated if you take on exercise that’s intense on the muscles, so again, walking is a great option, as is a gentle swim using breaststroke or backstroke. Other great options for fibromyalgia are yoga and tai chi, which include slow movements and little impact.

Take plenty of breaks

In addition to keeping exercise low intensity, take plenty of breaks. Not only will this allow you to recover energy levels, but you’ll actually be able to participate for longer, if you break your routine into smaller, bitesize chunks.

Listen to your body

Exercise can mean overcoming mental obstacles, no matter who you are, but when you suffer from fibromyalgia, it’s imperative you listen to your body. Don’t try to undertake exercise when the message coming from inside is ‘no’. There will simply be times when your energy levels are too low to participate in any form of exercise, so despite the mental frustration this will cause, listen to what your body is communicating.

Measure impact and recovery

Measure impact and recovery

Listen to what your body is telling you, and that means keeping tabs on it for two or three days after. As you start to build in exercise routines, do so gradually so the impact of each one can be measured independently. It will help you understand what is working for you, and what isn’t, and then you can develop routines that work for you.

“Although exercise tips are generic, and medical guidance is quite standard for fibromyalgia sufferers, the reality is that no two individuals will respond in exactly the same way to what could appear to be an identical workout, so continue to listen to your body, and continue with routines that work for you as an individual,” says Bruce Sorenson, a journalist at UKTopWriters and AustralianReviewer.

Additional tips

The nature of fibromyalgia means that there are related issues to look out for and manage with your workouts. One such issue is orthostatic intolerance — which means the blood rushes to the legs when sufferers stand up, and stays there. The solution to this is vastly increasing water and salt intake prior to and during exercise, and exercising in warm water. Using a recumbent bicycle can also greatly assist as a warm-up, or even as the exercise itself.

You should consult your physician or other health care professional before starting any exercise routine or program to determine if it’s suitable for your needs.

Aimee Laurence is a personal trainer and blogger at Paper Writing Service and Essay Service. She writes about Fibromyalgia and health. Also, Aimee tutors at Assignment Help Australia portal.

References

Pamela Chase, a Fibromyalgia expert, Simplegrad and Revieweal.

Bruce Sorenson, a journalist, UKTopWriters and AustralianReviewer.

Do you want to lose weight?

Do you want to lose weight? I give my clients a baseline of their body fat percentage and get them to use the scale. Then we set up a diet and exercise plan. You can lose weight by diet alone. But dieting can reduce muscle mass along with fat. This becomes ever more important as we age. We can lose as much as 6 pounds of muscle tissue per decade as we age. And metabolism can slow down as much as 3 percent per decade. You can see that if left unchecked, you’re on a slow boat to obesity. Adding an exercise program may be all you need to turn this process around. Cardio exercise burns calories, and strength training raises your metabolism and builds lean muscle mass while you are losing. Losing about 1 percent body fat a month and one to two pounds a week is considered safe and realistic. Here’s the winning combination. Reduce calorie intake with diet, do cardio most days to burn calories, and strength train at least a couple of days a week to build muscle mass and increase metabolism.

I give my clients a baseline of their body fat percentage and get them to use the scale. Then we set up a diet and exercise plan. You can lose weight by diet alone. But dieting can reduce muscle mass along with fat. This becomes ever more important as we age. We can lose as much as 6 pounds of muscle tissue per decade as we age. And metabolism can slow down as much as 3 percent per decade. You can see that if left unchecked, you’re on a slow boat to obesity. Adding an exercise program may be all you need to turn this process around. Cardio exercise burns calories, and strength training raises your metabolism and builds lean muscle mass while you are losing. Losing about 1 percent body fat a month and one to two pounds a week is considered safe and realistic. Here’s the winning combination. Reduce calorie intake with diet, do cardio most days to burn calories, and strength train at least a couple of days a week to build muscle mass and increase metabolism.

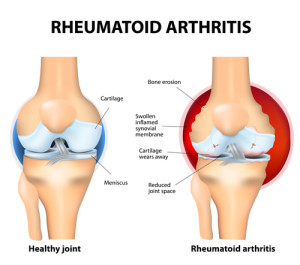

When left unchecked, rheumatoid arthritis can be majorly debilitating and cause real and continued pain. However, if you’re willing to do the research and put in the work, you can do certain exercises which can majorly reduce the symptoms, improve your overall mood and actually make you that much physically healthier, generally speaking, which can only be a good thing. The real question then is, what sort of exercises ought you be doing to try and achieve this. Well, let’s take a look at five ways to help improve those symptoms.

When left unchecked, rheumatoid arthritis can be majorly debilitating and cause real and continued pain. However, if you’re willing to do the research and put in the work, you can do certain exercises which can majorly reduce the symptoms, improve your overall mood and actually make you that much physically healthier, generally speaking, which can only be a good thing. The real question then is, what sort of exercises ought you be doing to try and achieve this. Well, let’s take a look at five ways to help improve those symptoms.

Like Cicero coining the phrase “Ipse dixit” (“He, himself, said it”) in reference to the mathematician Pythagoras, we tend to appeal to the pronouncements of the master (in our society, celebrities and the media) rather than to reason or evidence. After all, if Jillian Michaels from TV’s The Biggest Loser or any other celebrity trainer says it’s so, it must be so, right? This has led to the proliferation of many myths in the weight-loss and fitness industry. Why do we think or claim we know things that we actually do not know? There are so many passionate people in the weight-loss and fitness industry, which is great, but oftentimes that passion gets in the way of science. And that can be dangerous. Do you know your weight-loss facts from fiction?

Like Cicero coining the phrase “Ipse dixit” (“He, himself, said it”) in reference to the mathematician Pythagoras, we tend to appeal to the pronouncements of the master (in our society, celebrities and the media) rather than to reason or evidence. After all, if Jillian Michaels from TV’s The Biggest Loser or any other celebrity trainer says it’s so, it must be so, right? This has led to the proliferation of many myths in the weight-loss and fitness industry. Why do we think or claim we know things that we actually do not know? There are so many passionate people in the weight-loss and fitness industry, which is great, but oftentimes that passion gets in the way of science. And that can be dangerous. Do you know your weight-loss facts from fiction? Myth: Nutrition (diet) is more important than exercise for losing weight and looking good.

Myth: Nutrition (diet) is more important than exercise for losing weight and looking good.

Designing a Fitness Program

Designing a Fitness Program Plan of Action

Plan of Action