The Aging Athlete

If you’re reading this you are likely interested in beginning or improving in a recreational activity or sport. You might want to train for stadium football, a rec team, fun runs, obstacle courses or something as major as a triathlon. While you may be anxious to jump right into a training program there are a few things you should consider such as your current activity level, current physical condition (i.e. chronic conditions, aches, past surgeries, injuries), and knowledge of physical fitness programming.

Who is the Aging Athlete?

The aging athlete can be anyone who needs to rethink their recovery strategy as it relates to the rigors of the desired/continued activity due to the aging process. Likely this is any athlete or recreational athlete in their 30’s, 40’s and beyond. The National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA) states, that while the cardiovascular endurance and muscular strength of older competitors or athletes are truly exceptional, even the most highly trained athletes experience some decline in performance after the age 30. As such participating in recreational sports or activities fully depends on your health and preparation and the sport or activity you are pursuing.

Before you begin you should consult with your primary health care provider (PHCP). If you’ve been cleared but inactive for any period of time complete a physical activity readiness questionnaire (PAR-Q) to ensure nothing has changed. Additionally, if you have a chronic condition, chances are your PHCP has already discussed exercise with you, and most likely gave you some general guidelines. A chronic condition defined by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is a condition that lasts one year or more and requires ongoing medical attention or limits activities of daily living or both. This does not preclude you from participating in recreational sport or activity necessarily, but it is a factor to be taken into consideration. You may be asking yourself, is this something I can do? Is this something I can do on my own? Do I need a trainer? How do I know what trainer I should go to?

Is this something you can do on your own?

The answer is yes, with this caveat. Unless you have a background in exercise, likely there will come a point when you will need someone to reach out to for advice. If that happens reach out to a professional with the appropriate qualifications. Frequently, I have heard gym members echo comments questioning the validity or worth of paying someone to do something they can do on their own. They often do not realize or recognize that hiring a professional who is educated and experienced in strength and conditioning is more than just programming exercise, it’s also injury prevention. Activities, movements, or lack of recovery may not have caused injury in the past, but as we age the dynamic changes, and to remain healthy and injury free, we must change. Commonly people just work around injuries, avoid certain exercises, or reduce intensity and accept that’s just part of aging, so they press forward. However, if they would have consulted with a fitness professional they may have found a better more comprehensive solution.

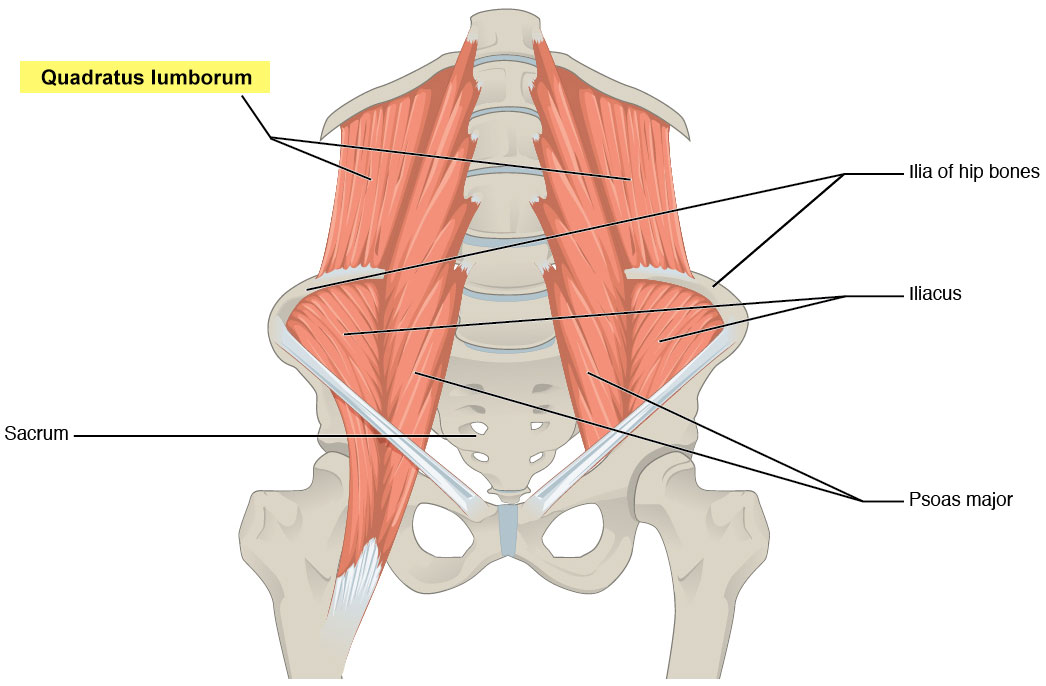

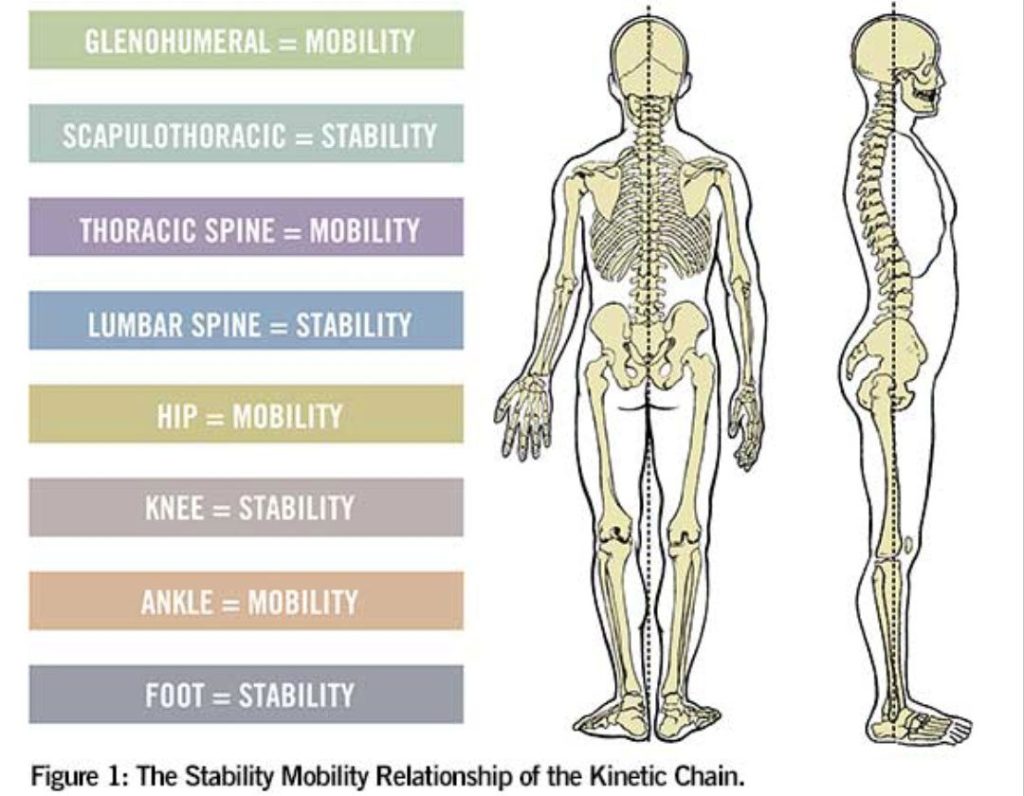

Working around past injuries is a useful and worthy approach, if done correctly. However, the truth is that most of those injuries are a result of their habits. Perhaps they have been predominantly inactive, spending much of the day sitting. Perhaps they were training hard without any or little variation in intensity, without any or little variation of joint movement, and without any or little variation in program design. These all add up to repetitive stress injuries. Common repetitive stress injuries often appear as bursitis, arthritis, tendonitis, and lower back pain/injuries.

That is not to say you cannot do this on your own nor that you need a trainer or will always need a trainer. It is to communicate the point that we do not inherently know how to exercise properly. Many in their youth have participated in sports, and the programs they were taught may be missing some crucial elements to keep them healthy and pain free. These elements are missing sometimes because years ago we did not have the information we have today. Sometimes it’s because we only remember some of what we were taught, and other times it’s because we have aged, or our physical needs have changed and require a change in programming.

If you’ve never exercised before, it’s recommended you either take a few classes (not a fitness class such as spin, but an instructional class offered at a gym, YMCA, or college) or hire a trainer for a short period of time. Perhaps you are on the fence on taking a class or seeing a trainer. If that is the case, ask yourself these questions:

Are you developing aches and pains that are lasting for longer periods of time?

Do you know what a plane of motion is, and how to exercise your joints in each plane of motion?

How often do you change your program? Do you have a chronic condition?

Are you developing lower back, knee, or hip pain?

The answers to these questions can give you a good sense of whether you may benefit from seeking professional assistance or instruction.

The Key is Individualized Programming

Assuming your destination is recreational sports and activities or even occupational activities the program should be appropriately progressed in intensity, duration, and specificity to get you to your desired destination. Repetitive stress injuries occur because one set of tissues in the body/muscle/joint continue to be challenged in the same way at the same spot over, and over again. By taking your occupation, past activities or recreational sports into account your program can be structured to bring the proper balance of strength, and flexibility to the areas that may be neglected or strained. Below is a list of general guidelines if you’re choosing to do this on your own:

General

- It is recommended you undergo a health screening by your PHCP prior to beginning

- Cardiovascular and resistance training are both recommended, intensity in both depend on your medical clearance, training status, and sport of choice

- Perform exercise through a full pain free range of motion, and do not exercise if the joint is in pain or inflamed3

- Listen to your body, and when in doubt seek guidance from a qualified fitness professional

Resistance, Cardio and Sport Specific Exercise

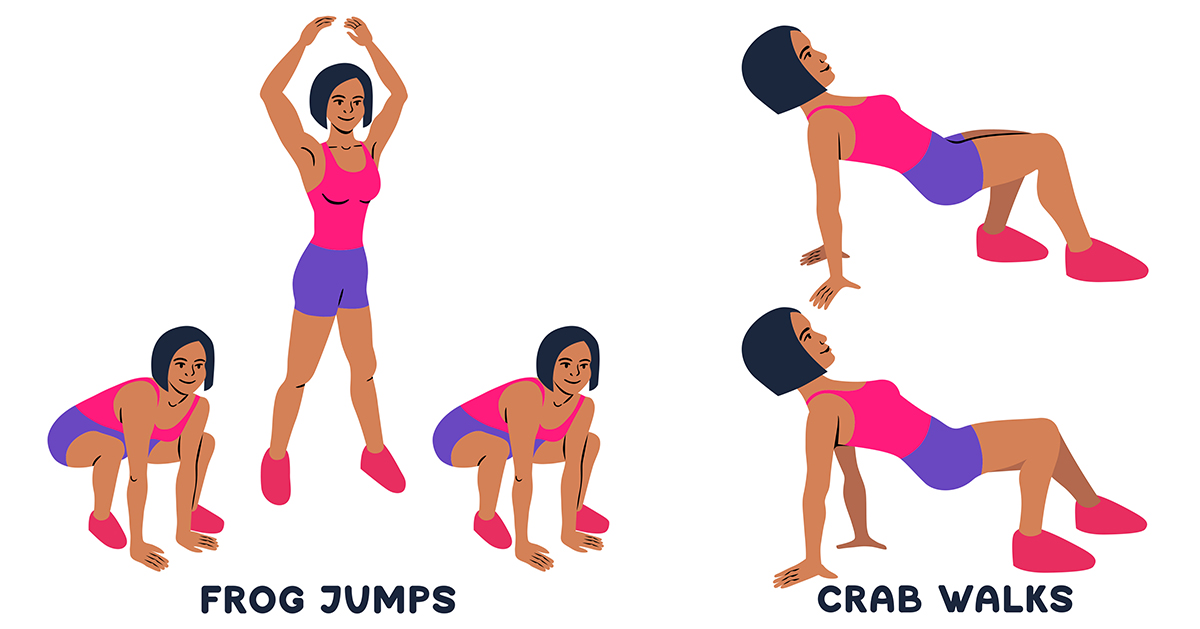

- Warm-up for 5-10 minutes with low-moderate aerobic activity and calisthenics, and perform static stretching after the warm-up and at the end of the workout2

- For cardiovascular/endurance perform 20-60 minutes of large-muscle aerobic activity most days at an intensity of 60%-90% of age-predicted heart rate1

- If you have been sedentary or are just beginning, resistance train no more than twice a week, allowing 48-72 hours to recover, as you progress you can workout daily with different muscles groups at different intensities each day2

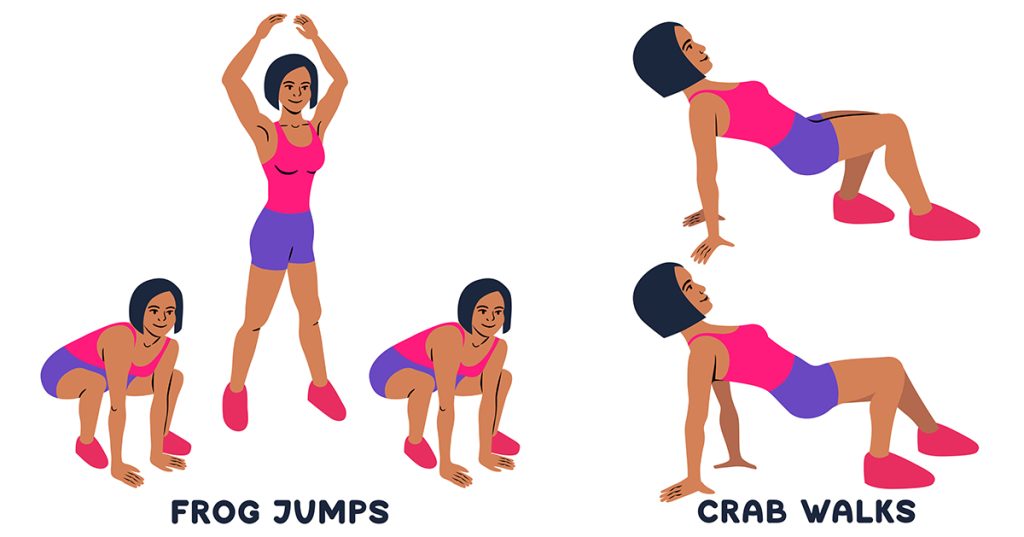

- Focus on mastering basic resistance exercises then implement exercises that are more sport specific, as well as balance, free weights, multi-directional, multi-joint, and power/agility exercises2

- Begin doing 8-12 repetitions of a weight that is equal to 50% of your maximum weight and gradually increase to up to 80% of your maximum weight, weight should be lifted and lowered in a controlled manner, and at a slower speed in the beginning (2 seconds for the lifting phase, and 2 seconds for the lowering phase), for 1-3 sets2

- Take 1-3 minutes of rest between sets3

- Avoid holding your breath during exercise2

- Once you’ve advanced to power/speed training, perform 1-3 sets per exercise at 40-60% of your maximum weight and 6-10 repetitions at a high (but controlled) speed2

- Train each joint in multiple directions (ie. planes of motion). For example, the hip can perform flexion, abduction, adduction, or circumduction.

What Should I look for in a Trainer?

If you elect to see a trainer there’s a few things you want to look for. You want a trainer with verifiable experience, an accredited certification/college degree, and liability insurance. The fitness industry is largely unregulated and there is some debate among which certifications are the best. A good place to start is the MedFit Network as trainers have to meet professional criteria in order to be listed. Additionally, it is important that their experience and background suits them to your specific needs. If you have a chronic condition, dealing with pain or have past injuries these are areas you want to be confident they can serve. As you are either engaged in athletic activity or want to engage in athletic activity it is important that the trainer have a solid foundation of periodization, and athletic performance. Quack science and self-professed gurus have no place here. The trainer’s practices should be founded in the principles set forth by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), and the National Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA). Most trainers offer a free assessment, which gives them an opportunity to learn about you, and you to learn about them. Be sure to meet with several trainers and ask for client references. This is a reasonable request and a quality trainer will not take offense. Lastly, if something feels off, seek a second opinion.

When undertaking rigorous activity and sport, there are other services you may want to consider, or discuss with your PHCP such as massage therapy, nutritional counseling, or chiropractic care depending on your needs. Remember one size does not fit all and by keeping your health in balance now you will be able to continue to enjoy the activities and sports you love for years to come.

Jeremy Kring, holds a Master’s degree in Exercise Science from the California University of Pennsylvania, and a Bachelor’s degree from Duquesne University. He is a college instructor where he teaches the science of exercise and personal training. He is a certified and practicing personal/fitness trainer, and got his start in the field of fitness training in the United States Marine Corps in 1998. You can visit his website at jumping-jacs.com

References

- Jacobs, P. L. (2018). NSCAs essentials of training special populations. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Haff, G., & Triplett, N. T. (2016). NSCAs essentials of strength training and conditioning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Brown, L. E. (2017). Strength training se/National Strength and Conditioning Association. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.