5 Surprising Ways That Your Job Influences Your Health

Different aspects of your life can affect your health. Exercise, food intake, and sleep are prevalent factors. Unknowingly, your job also affects your mental and physical health. You must consider it if you wish to live a healthy lifestyle.

You spend a majority of your waking hours at work. Several studies have pointed out that the work environment affects your overall well-being and relationships with other people. Let’s take a look at some of them:

Work Overload

Overworking can have adverse effects that include mood disorders, debilitating stress, and illness. If you have little control over your workload, you may experience burnout. According to the American Institute of Stress, 80% of employees and managers face stress at work that results from competition between coworkers, tense working environments, and a feeling of walking on eggshells.

The World Health Organization describes burnout as a type of chronic work stress depleting energy and diminishing efficacy. 50% of workers quit their jobs because of it. You tend to mentally disengage from your coworkers and become increasingly adverse about them. Cynicism with extended working hours drains your joy about working and increases exhaustion.

Depression and anxiety are also prevalent when you overwork yourself. Your moodiness can affect your relationships with your colleagues and supervisors. Overworking can also increase overall work dissatisfaction and heighten anxiety, and you also experience low self-esteem and have feelings of inadequacy. Your feelings of helplessness and restlessness can make you slip into depression.

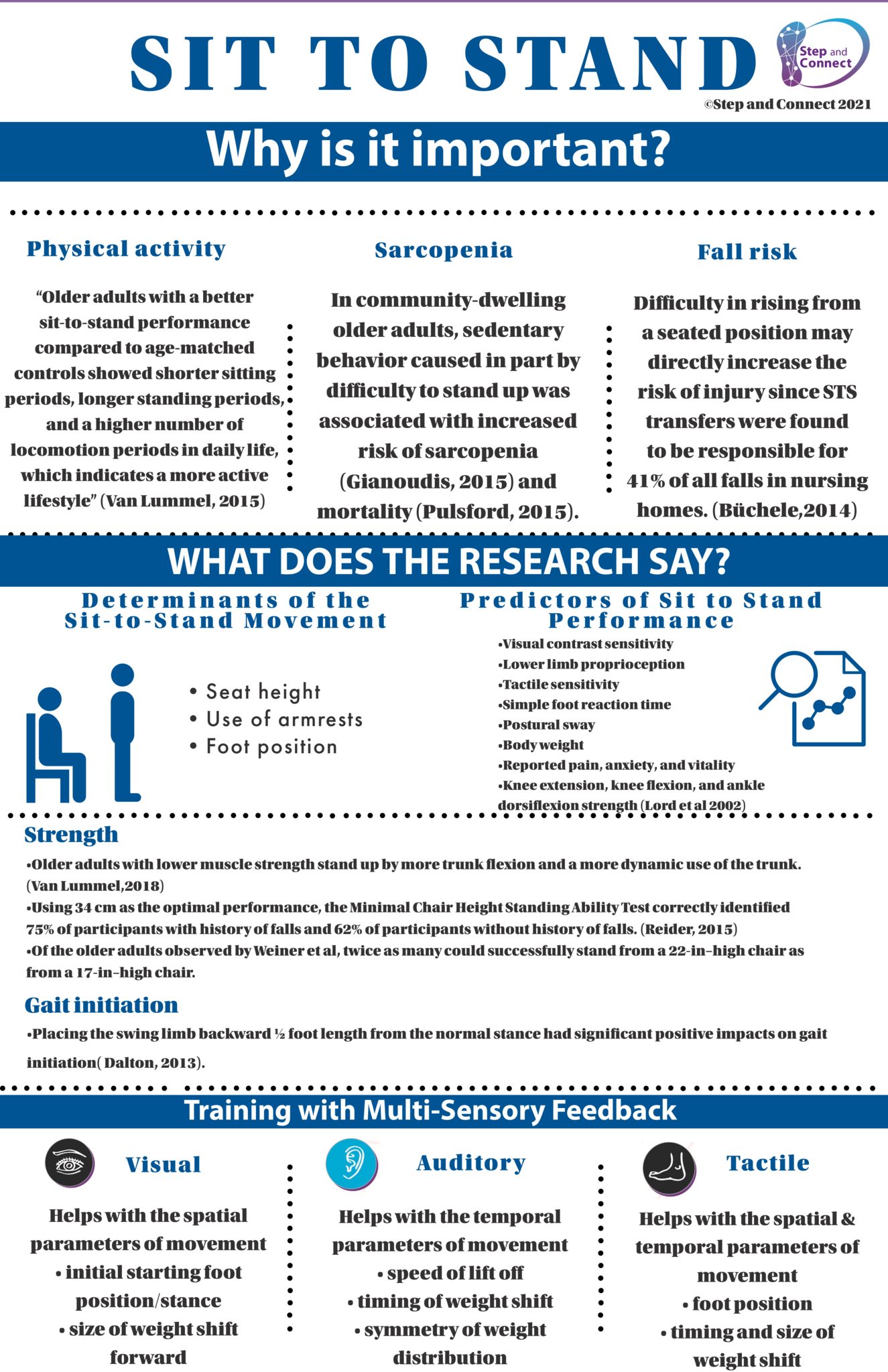

Lack of Physical Activity

If you work in an office setup, your lack of physical activity can result in several health problems. Your sedentary lifestyle can lead to muscle-related pain, fatigue, and diabetes. You are also susceptible to eye issues if you stay glued to your computer every day.

You often get lost in work and spend hours in your seat. If you suffer from constant backache, you now know why. Sitting in your office chair for extended periods can strain and overstretch your back muscles.

Hating Your Job

If you love your work, you are fortunate because you can pay your bills doing things you like to do. Unfortunately, if you hate what you do but stay in your job to pay the bills, you become unhappy and eventually suffer from stress and exhaustion.

The University of Manchester released the results of its study about poor-quality jobs. According to them, staying in a job you have can wreak havoc on your mental health. It is even worse than being jobless. A passive-aggressive boss, hostile co-employees, and mind-numbing tasks, together with spending more than 40 hours per week in your office, can worsen your situation.

If you are dealing with a mental health issue, you can experience stress, burnout, and exhaustion, especially if you cannot find other jobs or feel obligated to stay because you have bills to pay. Your loss of autonomy and feeling of indebtedness can be emotionally draining.

You feel stuck because your mental health issues do not allow you to find your way out. You do not have the motivation to search for alternatives. You feel helpless and hopeless to change your situation. Getting out of the trapped mindset needs a courageous effort.

Long Commute

The workday starts and ends with your commute. If you live in a large city, your commute takes longer. You become less happy and experience burnout quicker. Your daily commute is also a health risk as commute distance and time continually increase. As a commuter, you spend more than a total of 80 minutes getting to and from work.

The situation worsens if you must commute from one city to another. It increases your blood pressure. You experience heightened cortisol and adrenaline levels that raise your risk of a heart attack. Respiratory issues and air pollution exposure can also have acute effects on your health.

If you stay in your car for an hour’s drive to work, you are adding one more hour to your sedentary lifestyle. Lack of physical activity can lead to diabetes and obesity. Aside from the physical manifestations, an extended commute can also lead to listlessness, boredom, anger, and stress.

Although you can deal with them, you suffer from long-term chronic stress if such moments occur daily. Driving through traffic can result in expending more mental and physical energies that can be exhausting.

Interpersonal Relationships at Work

Establishing close connections with your coworkers is healthy. You are less likely to feel burnout and become happier if you have more camaraderie with your colleagues. Belonging to a group increases your sense of purpose, meaning, affinity, agency, and control. You become competent and productive at work because of your identification with your company.

However, if you have negative work interactions or experience bad bosses and bullying, your health can suffer. Loneliness can result in your untimely demise. Therefore, you must connect with other people in your company. If you can find connectivity with your bosses or coworkers, you can search elsewhere.