Pre-diabetes – A Wellness Opportunity To Help

There is an opportunity for wellness and wellness coaching to impact the lives of millions of people in a life-saving way. 79 million Americans are estimated to have a condition called pre-diabetes. Usually symptom free, without intervention they will develop full-fledged Type II diabetes within ten years and possibly endure physical damage to their heart and circulatory system along the way. Yet, according to the American Diabetes Association, if a person is successful at lifestyle improvement they can completely avoid the onset of diabetes 70% of the time.

“People with diabetes are living longer now, which is incredibly exciting,” says Rita Kalyani, MD, MHS, an associate professor of medicine in the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. But “it’s important to recognize [the potential for accelerated muscle loss] because it can significantly impact quality of life for people with diabetes and also mortality.”

“People with diabetes are living longer now, which is incredibly exciting,” says Rita Kalyani, MD, MHS, an associate professor of medicine in the division of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. But “it’s important to recognize [the potential for accelerated muscle loss] because it can significantly impact quality of life for people with diabetes and also mortality.” The presence of insulin resistance, which is the key feature of type 2 diabetes, appears to be a major pathway. “Insulin resistance is associated with decreased protein synthesis in the muscle,” Kalyani says. One of the key roles of insulin is to drive nutrients (ie, glucose) from the blood into skeletal muscle tissue and stimulate protein synthesis. In type 2 diabetes, however, insulin signaling is impaired; insulin is not able to effectively drive glucose into the muscle tissue, and the muscle cannot synthesize new protein rapidly enough to keep pace with natural muscle degradation.(13)

The presence of insulin resistance, which is the key feature of type 2 diabetes, appears to be a major pathway. “Insulin resistance is associated with decreased protein synthesis in the muscle,” Kalyani says. One of the key roles of insulin is to drive nutrients (ie, glucose) from the blood into skeletal muscle tissue and stimulate protein synthesis. In type 2 diabetes, however, insulin signaling is impaired; insulin is not able to effectively drive glucose into the muscle tissue, and the muscle cannot synthesize new protein rapidly enough to keep pace with natural muscle degradation.(13)

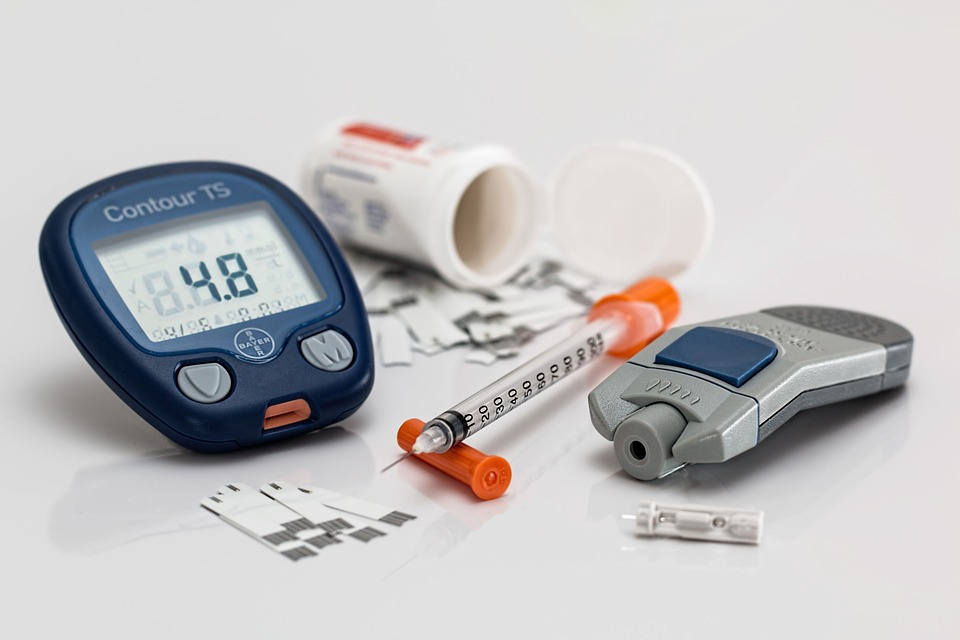

Diabetes, is left uncontrolled, can cause a whole host of health complications such as vision impairment and neuropathy. It is important to adhere to any instructions your doctor has given you to keep blood sugars controlled. Your physician may also educate you on exercise, diet and stress management to keep a balanced and healthy lifestyle.

Diabetes, is left uncontrolled, can cause a whole host of health complications such as vision impairment and neuropathy. It is important to adhere to any instructions your doctor has given you to keep blood sugars controlled. Your physician may also educate you on exercise, diet and stress management to keep a balanced and healthy lifestyle. When controlling stress, you need to find out what works for you personally. Some individuals like to take a walk in the park, others choose to practice meditation or use a combination of many techniques. When you start to try new practices remember that you may have to try each a few times. The body has to get used to approaches. A qualified stress management consultant can help you to create a stress management plan specifically for you.

When controlling stress, you need to find out what works for you personally. Some individuals like to take a walk in the park, others choose to practice meditation or use a combination of many techniques. When you start to try new practices remember that you may have to try each a few times. The body has to get used to approaches. A qualified stress management consultant can help you to create a stress management plan specifically for you.