Closing the Trust Gap: Are personal training certifications failing medical fitness?

For over 30 years, the alphabet soup of letter-bearing personal training certification companies like ACE, NASM, NSCA and ISSA have focused on providing education leading to a fitness certification. While the companies have differing audiences and missions, collectively they have failed to truly make the connection between the fitness industry and the healthcare industry.

Personal trainers tend to be health advocates (and sometimes zealots) who show up as the face of the fitness industry. They tend to actually live and practice the life they espouse. Most leave the industry quickly, but even as they leave personal training and continue throughout their careers they tend to retain their core values around fitness.

Listen to almost any group of personal trainers and you’ll hear them speak passionately about the value of fitness and the ability to help control or eliminate diseases like type 2 diabetes, heart diseases and some forms of cancer. For their more affluent customers, personal trainers are frontline soldiers in a battle for healthier living.

So, how is it that well-intentioned organizations that believe that healthier living improves lives and who have over 350,000 personal trainers working in America alone have been unable to connect those trainers to the next higher level of their mission? What has gone so wrong that the average consumer would more likely connect a personal trainer to an Instagram or social media influencer than to their healthcare provider?

In a recent ISSA survey, personal training buyers were asked what education or qualifications were required to become a personal trainer. Nearly 80% of those surveyed did not know. Fortunately, nearly everyone surveyed believed that some form of education or certification was required. Perhaps consumers would have the same answer if the question was asked regarding nursing or other healthcare positions other than that of a doctor.

In this situation and those like it in America, we are accustomed to trusting the person in the job has the knowledge, skills and abilities to do the job. We may not know how or why, but we have given them the magic ingredient — trust.

In our society, we fundamentally trust that by achieving the title of doctor, the holder will do no harm and will have the secret to curing what ails us. Do we trust that our personal trainer will do no harm and will have the secret to help us achieve our fitness goals? Not so much.

In the same ISSA survey, buyers of personal training were asked if personal trainers could help clients lose weight and 90% answered yes. When asked if personal trainers could help cure type 2 diabetes only 10% answered yes. There was an 80% difference when asked the same question in the context of personal training goals versus medical goals!

It would seem logical that if the same question was asked in the context of knee pain or joint pain and heart disease or blood pressure the results would be the same.

We trust that personal trainers understand how to improve our fitness, but we don’t connect our fitness to our healthcare. This is a trust gap.

This trust gap is the most fundamental issue preventing all of the subsequent steps which need to happen in order for medical fitness to thrive. There can be no insurance reimbursement or physician prescription of exercise as medicine as long as we don’t first believe our health is in our control and that fitness professionals can help their clients achieve results.

Today, even physicians who believe in exercise as medicine are reluctant to refer clients. Despite some of the most forward-looking physicians and groups bringing exercise and personal training into their medical practice, compliance remains spotty and reimbursement varies widely.

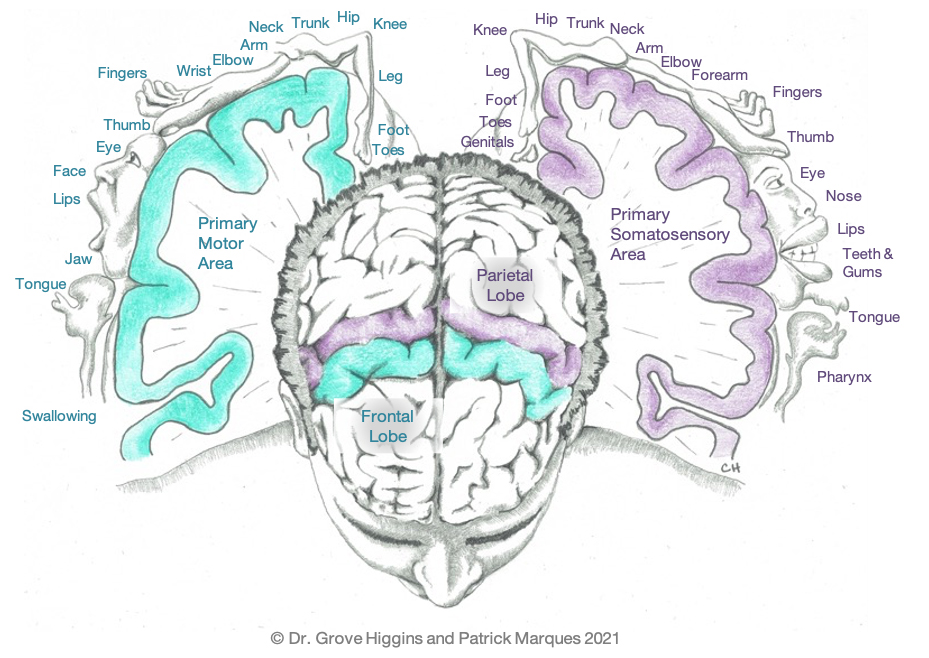

A recent study provided insights around prescribing exercise as medicine in the treatment of 26 different diseases: psychiatric diseases (depression, anxiety, stress, schizophrenia); neurological diseases (dementia, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis); metabolic diseases (obesity, hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, polycystic ovarian syndrome, type 2 diabetes, type 1 diabetes); cardiovascular diseases (hypertension, coronary heart disease, heart failure, cerebral apoplexy, and claudication intermittent); pulmonary diseases (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, cystic fibrosis); musculoskeletal disorders (osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, back pain, rheumatoid arthritis); and cancer.

But, how much of this is studied by medical students and applied by physicians? Why does the majority of our society doubt fitness? Is it because we don’t trust fitness professionals? If so, what is the fitness certification world to do?

If we are to close this trust gap, the industry needs to achieve three milestones:

- Personal trainers need to have a common standard of professional knowledge and skill

- Required continuing education and training must be in place

- We need to have standards of care for fitness programming.

This requires that the industry through leadership such as IHRSA combined with companies like ISSA, NASM, ACSM, ACE and others eliminate the need for individual exams and certifications and move to a common standard of excellence for all.

In the absence of the fitness industry creating an environment where all parties can trust their personal trainer to provide safe and effective training programs, none of us can expect medical schools to teach fitness or doctors to prescribe exercise or insurance companies to reimburse for exercise.

COVID-19 created a broad national awareness of the incredible risks of obesity and underlying medical conditions which largely could be controlled through diet and exercise. Now is the time to take action and help a new generation live healthier lives.

Andrew Wyant serves as the President of the International Sports Sciences Association (ISSA) after having helped successfully build and grow a series of businesses in a wide variety of industries. Since becoming ISSA’s leader in 2018, the ISSA has grown by over 400% and has become the No. 1 rated and reviewed personal training company in the world. Andrew is passionate about the potential personal trainers have to help improve our world by reducing the rates of preventable diseases. He has been deeply involved in the health and fitness industry since 2011.

This article was featured in MedFit Professional Magazine.

It’s unfortunate, but the average person has no idea what to look for in a trainer. They don’t know the questions to ask, the accredited certifications and whether or not that trainer is able to work with any pre-existing conditions that they may have. As gyms hire underqualified trainers, underselling those of you who are worth your fee, clients continue to get injured. The client goes to a physical or occupational therapist and tells them they’ve been working with a trainer at X gym. The therapist rolls their eyes, having heard the story time and time again, discrediting personal trainers and the fitness industry as a whole.

It’s unfortunate, but the average person has no idea what to look for in a trainer. They don’t know the questions to ask, the accredited certifications and whether or not that trainer is able to work with any pre-existing conditions that they may have. As gyms hire underqualified trainers, underselling those of you who are worth your fee, clients continue to get injured. The client goes to a physical or occupational therapist and tells them they’ve been working with a trainer at X gym. The therapist rolls their eyes, having heard the story time and time again, discrediting personal trainers and the fitness industry as a whole.

If fitness and exercise are well accepted as part of the management strategy for multiple diseases, why is it that access to organized exercise plans, and fitness professionals who can help implement those plans, are not a standard part of the medical treatment paradigm? Why is it not a standard benefit covered by common medical insurance policies?

If fitness and exercise are well accepted as part of the management strategy for multiple diseases, why is it that access to organized exercise plans, and fitness professionals who can help implement those plans, are not a standard part of the medical treatment paradigm? Why is it not a standard benefit covered by common medical insurance policies?