How to Turn Your Fitness Facility into a Health and Wellness Facility and WHY!

2020 came and went with a pandemic and the resulting crash of our fitness industry as we knew. It seemed like time stopped. Fitness facility doors closed. Staff were furloughed and separated. Fitness delivery models changed overnight – hybrid models of live streaming and on-demand services. Business plans were re-done for a budget year that evaporated.

The OPPORTUNITY… there has been an increased awareness of the value of good health and the importance of exercise. Much of the research shared post-COVID clearly demonstrated that the sickest were at the highest risk with COVID and that those who were mostly healthy fared much better when diagnosed with COVID.

CDC reported that obesity worsens outcomes from COVID-19. Obesity increases the risk of severe illness, tripled the likelihood of being hospitalized, and is linked to impaired immune function, decreased lung capacity and many other risks. Obesity is forecasted to exceed 50% in Americans by 2030.

How do we go forward as business owners to capitalize on a perfect storm of individuals now realizing and valuing their health as an asset? How do we go forward to create environments in which our facilities feel like a home away from home for new exercisers, de-conditioned, COVID recoveries, overweight, out of shape and scared individuals who now wish to exercise?

American Psychological Association reported recently that Americans’ Physical Health has taken a back seat since the start of the pandemic. It was reported that 47% delayed or canceled healthcare services and that 53% have been less active than they wanted.

How do we fill the gap to provide services and welcome all ages, stages, shapes, sizes into our facilities to capitalize the business opportunity and to support those who need us most to get healthier?

- Bring communities together by offering health and wellness programs to non-members that teach good health and prevention. Some examples:

- Post-hab COVID health program: 30 days to reset your health

- 8-week weight loss programs/challenges, 8-week pre-diabetes classes, 8-week cardiovascular health and wellness programs.

- Any program that can target a COVID risk factor that targets a certain element of health: cardiovascular, flexibility, strength, stress management, sleep, etc… or certain disease states such as asthma, obesity, diabetes, hypertension etc. all can be made into health and wellness programs for potential new members.

- Consider offering these health and wellness programs (with a nominal registration fee) without requiring a membership to your facility. So, include a membership to your facility for the duration of the program, offer a discounted sign-up fee to convert them to members at the completion of the program, and perhaps a friends and family rate to enroll. Leave a trail of financial incentive crumbs with some skin in the game to get them to value your facility and programs to stay long-term. Show them the value-added they experience by having you at your facility. Let them “try before they buy” — but in the wellness space first. Not “gym and swim” first…that is too much for some.

- Offer intro level and disease-specific type group classes that may group like-minded individuals with common goals. Example: Beginner cardio class, where you clearly accommodate beginners, new exercisers, those who are low-level fitness and who need a shorter duration of work.

- Offer personal training programs that clearly measure pre and post-health metrics to show improvement to give individuals confidence in their improving health and an appreciation of the value of the services they pay for. This also allows for your trainers and your facility to connect their improved health outcomes to their primary care providers so you can get future referrals as a credible source for a patient who needs exercise.

- Offer healthier food choices and nutrition education as part of your centers’ offerings. Consider adding a Dietitian to your team.

- Partner with local health departments, health care systems to host health checks to promote good health awareness and to get more foot traffic into your center.

THINK “A GYM without WALLS” and offer wellness to all – become the health hub of your community!! It makes good business sense for all!

Debbie Bellenger is a skilled presenter, public speaker, TRX Master Trainer and Reebok Master Trainer. Over the past 30 years, Debbie has been developing and delivering medical wellness programs in an integrated continuum of care model with providers using EPIC as a platform of referrals and communications back and forth. She also successfully developed a new service line for CaroMont Regional Medical Center called Employer Wellness services which sold over $500,000 of corporate wellness programs with coordinators to local companies.

Debbie is the 2014 Medical Fitness Association Corporate Wellness Director of the Year – Employee Wellness. She is the 2017 IDEA Program Director of the Year Award recipient, which recognizes a Director who develops and delivers health, fitness and wellness programs for employees, participants and patients that have successfully changed behaviors and demonstrated positive outcomes of improved health.

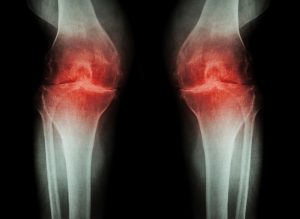

The rapid and dramatic increase in individuals living with osteoarthritis and/or joint replacements has created a massive void between the number of people living with these issues and the number of qualified individuals to help them safely and effectively accomplish their functional goals. This void, however, has created an incredible opportunity for fitness professionals to align themselves with allied health professionals to become part of the solution. This article will discuss some recent changes in the thought process about how osteoarthritis develops, how fitness professionals are an important part of the solution, and why this is the most opportune time for fitness professionals to specialize and align themselves with health professionals.

The rapid and dramatic increase in individuals living with osteoarthritis and/or joint replacements has created a massive void between the number of people living with these issues and the number of qualified individuals to help them safely and effectively accomplish their functional goals. This void, however, has created an incredible opportunity for fitness professionals to align themselves with allied health professionals to become part of the solution. This article will discuss some recent changes in the thought process about how osteoarthritis develops, how fitness professionals are an important part of the solution, and why this is the most opportune time for fitness professionals to specialize and align themselves with health professionals.